ANARCH

Video accompanying the lecture of Peter Mark Adams on Gast Bouschet’s book Anarch, published in collaboration with Scarlet Imprint, at the Metamorphosis – Ecstasies of Matter & Image conference at the University of Copenhagen on 31 May 2024.

Text by Gast Bouschet

Selected & narrated by Peter Mark Adams

Produced by Darragh Mason

Sound. P:R:I:S:M by Sutekh Hexen & Funerary Call

Many thanks to the University of Copenhagen for hosting the event, to Kevin Gan Yuen for the permission to use the music as a soundtrack and to Alkistis Dimech & Peter Grey of Scarlet Imprint for providing the images for the slideshow.

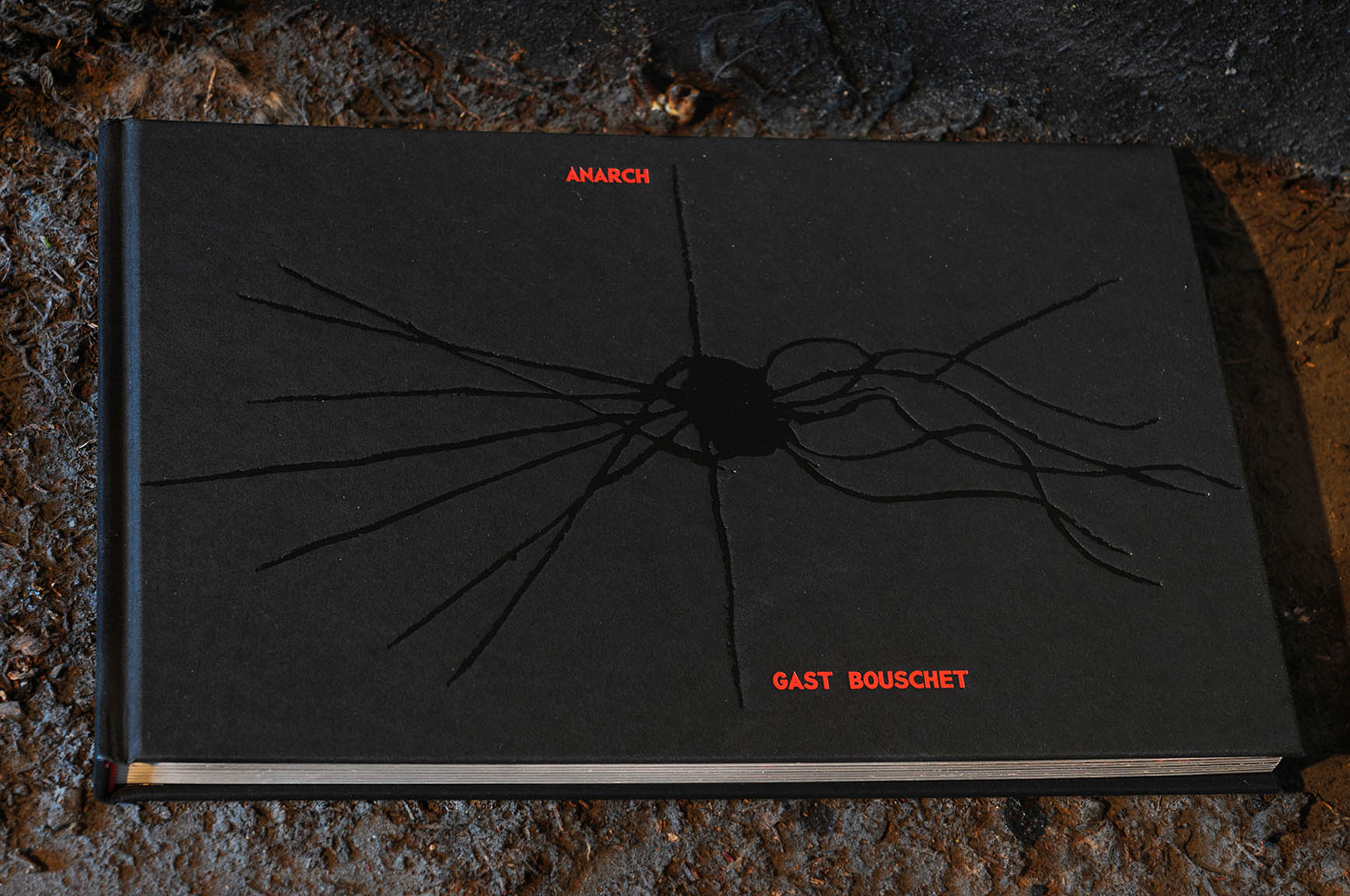

Published by SCARLET IMPRINT in 2023.

Anarch is issued in a strictly limited hardback edition of 800 copies.

4vo (195 × 300 mm)

160 pp

100 colour images

£69.00

Order

Contents

Nemesis (First Among Perils)

Jason Mohaghegh

The Mirrored Ladder of Strata

Stephen O’Malley

Letter to Sorcerers

(Here Too There Are Stars)

What Dreams! Those Forests!

Here’s the Prophecy

Soiled by Rebel Powers

Part 1: Toward a Dark Sacred

Part 2: Revolutionary Withdrawal

Alchemical Futures

Some basic reflections on the images included in this book

Only Chaos Sings the Truth

Forest, Forest, Forest

(Until My Blood Contains All)

Description

Anarch is a profound work of sinister animism and sorcerous practice, a unique account of the path taken towards the dark sacred in a lifetime of personal struggle and artistic creation.

Gast Bouschet is a singular artist, who has gone from desecrating the white cubes of the contemporary gallery space to a withdrawal into the crucible of forest from which issues his howls of vengeance, and potent spells against the excesses of civilisation.

Anarch collects a sequence of Bouschet’s excoriating elemental texts, which attest to his journey from the gallery shows of the international art circuit to a withdrawal into the primordial darkness of the forest and an encounter with power. Rejecting commodified art and the restrictions of a capitalist market he proposes an occult art, a counter-poison. Engaging with the non-human world of microbes, larvae, disease and predation, he shows how ‘the radical otherness of Radiant Darkness teaches us the demonic art of living beyond the edge of a fixed form.’

Bouschet discusses his techniques, practices and meditations; and shares diary extracts, revealing the signs and sacrifices he receives and undergoes. Here is the true black alchemy of the Sol Niger and the Saturnian current laid bare.

The texts lead us inexorably to the encounter with the works: 100 moments are exactingly reproduced in full colour, as they decay and are transformed by the forces of the forest. Fetishes, animal remains, paintings, spellbooks, moments of epiphanic revelation draw us into the tortured guts of the Ardennes which bask beneath the splendour of a black Sun. He writes,

‘They exist somewhere between the living and the dead: elementals, bacteria and fungi inhabit them, dragonflies land on them, birds shit on them, rats and mice feed on them, spiders weave their webs around them, insects lay their eggs inside them. Sorcery is a dangerous and messy affair as it brings together what is supposed to stay apart.’

Anarch transgresses the boundaries of the human experience and confronts us with the abyss. It is the epitome of what has been described as ‘black metal theory,’ is an example of Artaud’s theatre of cruelty, and Bataille’s base materialism. Defying even these categories, Anarch is ultimately a work of clandestine sorcery and ecological resistance, and an unrivalled record of contemporary magical artistic practice.

The book is prefaced by writer and philosopher Jason Mohaghegh and by Bouschet’s longterm collaborator Stephen O’Malley of Sunn O))).

– Peter Grey and Alkistis Dimech https://scarletimprint.com/

Anarch reviewed by Peter Mark Adams.

What motivates us is the intense, physical experience of life itself. The dark arts are an expression of a philosophy of alterity, a politics of heresy and a metaphysics of revolt that aims to change our being in the world. (p. 2)

ANARCH documents an ongoing process of profound personal transformation mediated by a four year long retreat in a forested landscape. Captured in fine writing and immersive photography, I cannot sufficiently commend the profundity of conception and execution that characterises this work. Under different conditions, this content would have found its rightful place as an installation, a combination of text and image, in a major exhibition space, biennial or art gallery; instead, ANARCH is that major art installation in the format of a book specifically – and I may say, beautifully –designed to showcase it.

Its author/artist, Gast Bouschet, is probably better known to the reader from his and Nadine Hilbert’s BPS22 Metamorphic Earth project wherein Alkistis Dimech performed the buto sequence, The Figures and the Signs of Night. The book itself – as with all of Scarlet Imprint’s works – fuses compelling content with the highest standards of presentation to showcase this important work.

ANARCH documents a four year retreat undertaken in the Ardennes Forest to which end it employs a tripartite structure: ten confessional “letters” addressed to “friends and allies”; a short section of aphoristic utterances culled, as far as I can see, from the roughly worked pages of notebooks that also feature, all too briefly, in the third section of this project; some one hundred pages of colour photography that document the landscape and assemblages that resulted from this longstanding creative engagement with the land in the enactment of a sorcerous alchemy of inner transformation. These striking, impactful images (mere words cannot capture or substitute for their forceful presence nor do them justice) need to be experienced to be properly appreciated since they lay at the very heart of the entire project; and serve to draw the reader, ineluctably, into the sorcerer’s liminal realm.

The ten “letters” enjoin inclusivity, proffering an invitation to engage as correspondents rather than anonymous “readers”,

Dear friends and allies,

Do you know what the dark arts are to me?

Poisonous beauty hovering in suspense, over the abyss. The awakening of a deeper identity. A complex relational field of both terror and redemption. A roar of raw elemental power. The light of blackness itself. (p. 3)

As these words suggest, each communique is exquisitely crafted to express the profound states of introspection that accompany the alchemical workings; penned months apart over the course of the four year retreat, each bears a date so that in registering the elapse of time the texts engage the reader in a developmental narrative charting the author’s evolving responses to his unfolding magnum opus.

The four years of this retreat were initially imposed by an accident that made the life of a professional artist no longer physically nor, in the face of the institutional demands of the corporate art world, ideologically or aesthetically, viable. The chosen arena, the Ardennes Forest – one of Europe’s “killing fields” and a site of intense industrial exploitation –bears both the psychic and physical scars of its history; and as such stands as both examplar and metaphor for the condition of the planet itself.

The blackness of the universe is the base matter out of which all things come and to which all things return. (p. 15)

It is this submission to the Saturnian current, the black sun, that provides the psycho-physical continuum – the alchemical alembic – for a sustained enactment of the “blackening” or “Nigredo” phase for,

Sol Niger is a symbol of interpenetration, continuous multiplicity, and eternal generation that does not point to a beginning or an end, but rather to a timeless substratum underlying biological and geological time. When we summon the Saturnian current into our innermost self, we make it participate in who we are. (p. 20)

It is this state that facilitates the transformations in the being of the artist that he fervently seeks as he engages with the intertwined realities of a shattered landscape and the enduring pain of physical disability,

Our sorcerous task is to become something else, something beyond the human, to transform into the flow of change itself. (p. 4)

As the illustrative material makes clear, working the fauna and flora, insect and animal life into organic assemblages of living and dead matter has less to do with the production of a recognisable art; and everything in common with the fetishes and jujus that manifest the sorcerous intent of dark alchemies wherein the very being of the alchemist is transformed through a creative absorption within the organically evolving processes; and in so doing, progressively dissolves the layers of the persona allowing the emergence of an other-than- human awareness,

What I would like to propose is an art and thought that does not aim to psychologically or spiritually overcome chthonic blackness, but to channel the transformative possibilities that grow out of it. Saturnian Alchemy is dirty and belongs to the earth, it does not avert impurity, but rather lures disruptive powers into physical things and bodies. The aim is not the purification of matter and consciousness but the transmutation into the multiplicity of nonhuman otherness. (p. 20)

So central is the inner alchemy of transformation to this project, and, indeed, so all- embracing is the polysemic metaphor of the transformative to this oeuvre; as the author seeks to identify with the hidden currents that drive both growth and decay, the meta-theme of becoming “other” runs through the work like a leitmotiv until,

I no longer felt myself as an individual with a single awareness, but as a profusion of beings and selves who expanded out into the depths of forest. (p. 5)

From the outset this work – with its masterful blend of fine photography, fine writing and fierce engagement – made me think of that other masterwork of sorcerous intent – Austin Osman Spare’s Book of Pleasure (London: Cooperative Printing Society Limited, 1913). Even though these two works are as aesthetically and literarily divergent as its possible to imagine; nevertheless, they are both imbued with and exude the distinctive frisson that the presence of “Promethean Fire” stamps upon, and serves as the hallmark of, all creative engagements with essentially otherworldly subject matter.

By virtue of its morphemes – “an‘” (“without”) and “arch” (“rule[r]”) – ANARCH is redolent of an intrinsic liminality that characterises the world of the shaman – a being who traverses the invisible boundaries between worlds; between the human and the other-than-human; between the living and the dead; but in doing so lights the path, illumines the way for those inspired to engage in equally precarious pursuits of self-reconstruction. And it is due to this fact that I finally gain that sense of completion emanating from the dark, difficult ways opened by these explorations; they demonstrate a particular case of that severe apothatic path of radical self-abnegation that is the hallmark of Saturnian metaphysics, a path that clears the way for the emergence of other trajectories and ways of being that we find captured in Deleuze’s concept, “becoming animal”; the experience of radical alterity that engenders a “line of flight” – a form of inner freedom – that is, and always was, an inherent part of our deepest nature,

Words can never fully describe the closeness with forest-dwelling powers that I experience in my night-time rituals, but if these lines help to advance a mythos that changes the way we perceive ourselves in relation to planetary others, my work here is done. (p. 18)

https://www.paralibrum.com/reviews/anarch-by-gast-bought-reviewed-by-peter-mark-adams

Anarch reviewed by Frater Acher.

A dream: I am wearing a mask frozen to my face. No one around me seems to notice. I am surprised by the stiffness of the chin piece and wonder if it will adapt to my natural movements or if it will remain as rigid as it is now. To avoid attracting attention, I act as if it were a human face, but it is not. (p. 36)

Gast Bouschet has given us a book about the place where death and life are interwoven in a Round Dance of day and night, interpenetrating and scratching at each other, deeply entangled. For Gast Bouschet, this place is a forest in the Ardennes. Or, rather, Gast has fallen from the physical locus of a forest in the Ardennes into this place of art and sorcery.

Now a forest can be entered from all kinds of directions. Unlike a house, it needs no gate or door to mark its thresholds of wood and thicket. The walls of a forest are also its passages; and so it lies at once open and closed to the approaching wanderer in all directions.

It is the same with Gast’s book, which is about, inspired by and born of a sorcerous forest and seems to have taken on many of its characteristics.

ANARCH can be read as a revolutionary manifest against the modern art world; a synthetic and yet brutal realm, suffocated by exploitative curation and capitalist investment strategies. Equally, ANARCH can be approached as an initiatory passage into the chthonic body of the underworld; a body that encounters eroticism, pain and delight just as much in decay and death as in germination and birth. Or ANARCH can be devoured as a satanic celebration of the black sun, the alchemical principle which does not offer light and warmth, but dissolution and decay, in order to break open objects – and this includes human bodyminds – for their flesh to be permeated by a lived understanding of the Other.

In all three of these ways, this book is a deeply personal testimony of an artist who became a sorcerer, and a sorcerer who turned into an undead. And it is in this notion of being undead that at least this reviewer found the charm, the sting, the depth and the delicious confusion of this book. Because it is precisely in the uncanniness of ANARCH that we also encounter its hope of a rediscovery to participate in this (under)world in a more authentically human way.

When Bram Stoker coined the word “undead”, he was inviting us to rethink the polarity of life and death, to break it open, and to make room for transitions and in–between states that are no less significant in their ontological presence than the one–dimensional declarations of being either dead or alive.

As such, an undead is one who is as familiar with life as with death. Their culture is at once sepulchral and passionate, marked by pain and yet life-affirming, profoundly transient and yet insisting on participation. Gast’s works now transport this original thought of the undead into the black horizon that straddles the concepts of art and sorcery. A habitat, as the book goes to show in words and images, animated more by disturbing and unruly than by aesthetically flattering artefacts.

ANARCH reminds me of the image of a palimpsest made of one’s own skin and written in one’s own blood, illustrating various layers, crusts and scarring of one’s own life and death. No human being is just one thing, one identity or one body at a time. We tear apart and we stack up. We are always legion. And in our best, most painful, most intense moments, we are no longer a body sealed off by membranes of skin and thought, but we begin to spill, to bleed, to eviscerate, to mingle wounded and wide open with our environment… In this sense, when it comes to entering the forest that is ANARCH, it is not “the crack that lets the light in”, but the wound that lets us out and into the wilderness around us.

To read this book with the right attitude – or to gain the right attitude by reading it – Gast invites us to imagine an alchemy no longer bound to the one goal of creating gold. Not to force nature beyond itself, as Julius Evola once put it, is the concern of this black alchemy, but to decompose bodies, to open bodies so that new encounters from within and without can take place. One has to imagine such an alchemy as an anarchic process, as a radical intervention, without a beginning and without a goal and without lab assistants or human supervisors. Rather, imagine it as a landslide or a festering wound. As something that – whether in frenzied, blind violence or in slow inflammatory decomposition – goes its very own way, insists on it, irrevocably, and carries the human being with it, as it were, as hostage in the far periphery of its undertaking. Here humans are no longer co-creators, certainly not semi-divine gardeners or living pinnacles of creation themselves. Rather, we are a skin pocket filled with delicious provisions for which a horde of micro- and macro-predators is already eagerly waiting.

Such black alchemy, or alchemical sorcery as Gast calls it, has a good chance of ending with the death of the people involved in it. So, like reading this book, it is not a light undertaking, not a preparatory school, and certainly not a human-centred anthropomorphic art. Instead, it is existentialist art of a kind one could hardly imagine more drastic, more radical.

Gast’s images that bear witness to this speak volumes, and yet they are no more than glimpses through a keyhole into the wilderness beyond.

Several times Gast emphasises that he is not giving a detailed transcription or instruction of his own magical practice. At the same time, he implies that such a practice would touch on several taboos of Western cultures as well as be resonant in many ways with African Vodun cults and their understanding of corporeality. The reader who is well versed in the subject can imagine everything else, and enjoy the fact that Gast thus spares his book the fate of being read as a modern, possibly even black magic “grimoire”.

Nothing is further from this book than to present a grammar of either environmentalist white or satanically black nature. Rather, it thrusts the reader backwards into a pit, dug in a remote, abandoned patch of forest, where we come to lie among earth, roots, leaves and decaying animal bones – oh yes, and also next to our author himself. In this kind of sacrificial intimate communion, Gast then takes us into his chthonic underworld.

To get a glimpse of it, I recommend imagining meditating with a festering wound and feeling deep peace. I recommend imagining lying in a forest clearing at night with an open cut, feeling more “with yourself” than ever before. Or imagine lying on a mattress in a forest hut with chronic pain, and feeling a joy that is not born from the absence of pain but from an entirely different encounter.

Now we, as readers, will not have much joy with ANARCH if we are not prepared to engage with such paradoxical situations and sensations. The core of this book is to “shift” our point of view so that we can see that these apparent paradoxes are but simple illusions. Illusions born of the at least three-thousand-year-old fantasy that the world has to subordinate itself to man.

For many Western recipients, it was Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) who began to radically expand the concept of art in the 1960s. Not only did he design his own biography as a work of art, i.e. he pierced the membrane between himself as a human being and the art surrounding and created by man. But, he broke a hole in the thick walls of museums and brought art into the social space. Above all, however, it was thanks to Beuys that the concept of shamanism was introduced into the concept of art and that the natural and animal raw materials he used were once again understood as materia magica.

In this sense we definitely find animistic echoes of the spirit of Beuys in Gast’s works; however, in an uncompromisingness that is completely appropriate in the face of the collapse of the human habitat in which we have found ourselves since the 21st century at the latest.

Gast’s ANARCH, one might say, brings the spirit of Beuys down into chthonic depths; brings it to lie beside us, as it were, in the sacrificial pit mentioned above. From there, Gast’s book buries us alive, takes us on a satanic–alchemical journey to leave us injured, wounded, and fully given over to transience as undead revenants in the 21st century in new and diabolical forms. And it is in this undead form that we see a new understanding of humanity flash forth. That is, if we are willing to surrender to the spirit of this book in its radicality.

Beuys’ wax, felt and animal skins, which unsettled the white space of the museum and pierced it with their presence, have, with Gast turned into roots, blood, earth, ashes and a hive of living forest presences as his sorcerous artist collective. Only the museum itself has been left far behind in Gast’s current works. It is, after all, the notion of curation to which they declare partisan war; may such curation take place in museums, temples, or books. Gast’s work cannot be separated from the vivid black background from which it emerges. No longer is the art cut out from its living ecosphere and curated for display, but the viewer themselves is thrown into the role of the intruder. With our touching of the book and glancing at its wild and dark images, it is we who break into Gast’s art, stir it up and disturb its natural process of transformation.

Gast’s photos of his decaying artworks out in the forest are at once vulnerable and wounding, soft and poisonous, like the touch of a fungal spore whose landing on our skin is imperceptible, yet crossing the fragile threshold of our skin unhindered. Gast’s photographs are undead in the original sense of the word: like scar tissue or cornea, they still belong to a living body and yet already carry the seeds of death within them. They point us towards a black horizon that stretches out underneath their paper-and-ink skins, at once wide open and completely closed in on itself.

Throughout ANARCH, the impenetrability of the subject for the unaffected outsider is beautifully balanced with the intimacy in which Gast presents his work. On the roughly 120 pages of written texts, however, it is Gast’s own voice that lends a timbre of familiarity and mutual proximity to the book that is a magnificent accomplishment in itself.

The texts develop from Gast’s arrival in the forest in the Ardennes to more advanced works in the following years. The fact that the author and publisher have preserved the authentic sequence of the texts’ creation and made it visible through inserted dates allows the reader to walk in perceived unison, slowly, with many pauses, together with Gast through the enchanted forest of his life and work.

Even in its most sharp and poignant moments, the text in this way always remains vulnerable and ephemeral, like Gast’s artworks themselves, which by now have been many times drenched by the seasons, soaked, frozen through, and are finally wearing their bones on their skin, or simply have been scattered by wild animals.

ANARCH is not about theoretical paradigm shifts, practical instructions on sorcery, or putting any specific thought or object of substance into the reader’s hands. Instead, this book wants to enchant us and it succeeds masterfully. Clearly, this is not the enchantment of romance but that of the ancient, archaic necromancy which turns the undead restless and might awaken some of them.

May this book walk through many hands, taking from them something of life and giving something of death. May we, with Gast Bouschet’s help, rediscover our own wounds as the places where we meet an unknown world, and from where art and sorcery break their untrodden way.

https://www.paralibrum.com/reviews/anarch-by-gast-bouschet-reviewed-by-frater-acher

Anarch reviewed by Mark Nemglan.

What is the role of the artist? Answers to this question are often framed in terms of utility: the artist’s role is to provide service to the society in which they operate; to record and document, to communicate, to interpret, to impart meaning – all for the benefit of the community. But what happens when the artist rejects society; its norms, morals and its values? Or extracts themselves from it, becoming located in a place outside and beyond? What is the role of an artist no longer in the service of society? And what of the work they produce? Surely ‘art’ only exists within the culture that endows it with meaning and value; outside a society’s culture, art becomes something wholly different.

At the outset of this compelling, insightful and surprisingly readable book, Bouschet confirms his status as an artist, and situates himself in relation to society in general, and the contemporary art world in particular. He observes that art-as-product accrues value in direct proportion to its visibility, to its reflective sheen and refractive index. But Bouschet’s art is occulted; hidden, withdrawn, obscure, abstruse, other. It has little value by the current art market’s standards, but it is of immense value to those who, like him, have rejected society’s norms, morals and values, and become antinomian.

Bouschet proposes a theory of art-as-sorcery, where antinomianism is a prerequisite. Unlike the shaman, who traditionally performs a magicko-religious function within, and for the benefit of, a community, the sorcerer stands alone in the darkness, in congress with the invisible realms for their own sake, unburdened by any social obligations. They are no longer part of the human communitas. Thus, Bouschet extricates himself from society and withdraws to the Ardennes Forest where, over a four year period, he experiences an alchemical blackening and transmutation. It should be noted that the Ardennes Forest is larger than the entire English county of Suffolk. It is a wilderness on a scale many of us can barely comprehend.

In doing so, he ensures that art returns to its primordial function and becomes magickal practice. The first artists were glyph-makers; shapers of alternate realities writ on the walls and ceilings of caves. They made the internal external; they reified, created, manifested. They revealed the hidden and gave form to the numinous. They reached into other realms to which art has now lost all connection. The first artists were sorcerers.

Thus, Bouschet’s primordial sorcery-art is one of silence and solitude, of humility and dissolution, of ego-loss and permeability, and ultimately of ecstasis. It is a practice that is empathic, immanent; one that becomes united with the undifferentiated blackness of the forest and, in turn, hollows out its subject.

It is a process that yields an alchemical transmutation into the multiplicity of non-human otherness; an otherness that resides as much within as without; in the microbial communities, biomolecular networks and bacterial ecosystems of our interior. All have agency, all are us and not-us. If we are legion, who are we but organisms haunted and possessed by the in-dwelling presence of billions of independent yet interdependent lives? By developing a propinquity with these alteric entities, Bouschet connects to the stuff of the earth, the chthonic materia which in turn yields a kind of bio-gnosis. Heraclides Ponticus conceived of the soul as a physical organ; illumination was achieved by way of one’s bodily faculties. Similarly, for Bouschet the soul is the non-human otherness that dwells within the body, and magical power may be drawn from organic materials – a state of affairs enshrined in his fetish-like sculptures which radiate telesmatic potency.

Bouschet’s writings are a manifesto for a sorcerous art primordial in its obsessions but forward-looking rather than regressive; a dark and Promethean art that confronts the earth’s geopathy unflinchingly. It is an art that responds to a civilization limping into an epoch of permanent crisis and upheaval, and so it must work directly with the poisoned and crippled world upon which we all now stand. Bouschet’s own spinal trauma and chronic pain are employed as a vinculum to the toxic paroxysms of Nature. They serve as a microcosm of planetary trauma; through the practitioner and their symbiosis with the world, both art and sorcery have personal and planetary consequences.

Amongst this blackened, tangled and bloody sorcery there is revelation, but it is not through an ascent to the celestial realm. It lies instead in a descent to the organic galaxies that lie within, and to the darkest chthonic depths of our ecology.

The book itself is generous in dimensions: large-format landscape, with Bouschet’s writings occupying one third of its contents. The remainder presents a photographic record of his sorcerous interventions; arresting, violent, benighted, darkly vaulted and crooked assaults on the eye; a visual grammar / grimoire describing a new magick for a dying planet. Read it and weep.

https://nemglan.com/review-anarch-by-gast-bouchet/

Anarch reviewed by Magister Clavus

Sinister Animism – Disturbing art by Gast Bouschet

This book will not teach you about magic. It will make you feel it.

Check out the review here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=huHnUVX1lRk

Film interview with Gast Bouschet

Exploration of the metaphysics of matter that underlies Anarch and Bouschet’s art and sorcery in general.

Director: Yannick Franck

Videographer: Camille Filleux

Sound engineer: Antoine Vandendriessche

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvnLMtwLzt8

My heartfelt thanks to hosts Graham and Snappy, whose wonderful podcast Searching for Dragons introduces historical and contemporary artists and sheds light on life and artistic creation from a magical perspective. Their fifth episode is entirely dedicated to my book Anarch.