LISTEN TO YOUR HOLES

LISTEN TO YOUR HOLES VIDEO IN “MEMORIAS INTIMAS MARCAS”

MUHKA ANTWERPEN, 2000

Curator: Fernando Alvim

“The exhibition which will be presented in MUHKA, constitute a part of the multi-medial project Memórias Intímas Marcas (Personal Memory and Traces). In addition to an exhibition featuring contemporary African art, this project also contains a CD, a documentary, a book, etc. It has been presented for the first time in 1997 and has travelled around the world ever since.

The point of departure of Memórias Intimas Marcas was the follow up after the war in Angola, but the artists attempt to extend there approach to other problems. Every display differs from the previous one because of the evolution of the theme of the exhibition and because for each and every show different artists are invited to participate.”

The artists which have been selected for the presentation at MUHKA are: Fernando Alvim (Angola), Bili Bidjocka (Cameroun), Willem Boshoff (South Africa), Gast Bouschet (Europe), Abrie Fourie (South Africa), Carlos Garaicoa (Cuba), Kendell Geers (South Africa), Kay Hassan (South Africa), Aimé Ntakiyica (Burundi), Toma Luntumbue (Kongo), N’Dilo Mutima (Angola), Colin Richards (South Africa), Jan van der Merwe (South Africa), Minette Vári (South Africa).

Memorias Intimas Marcas

(Anne Pontegnie, ArtForum, May 2000)

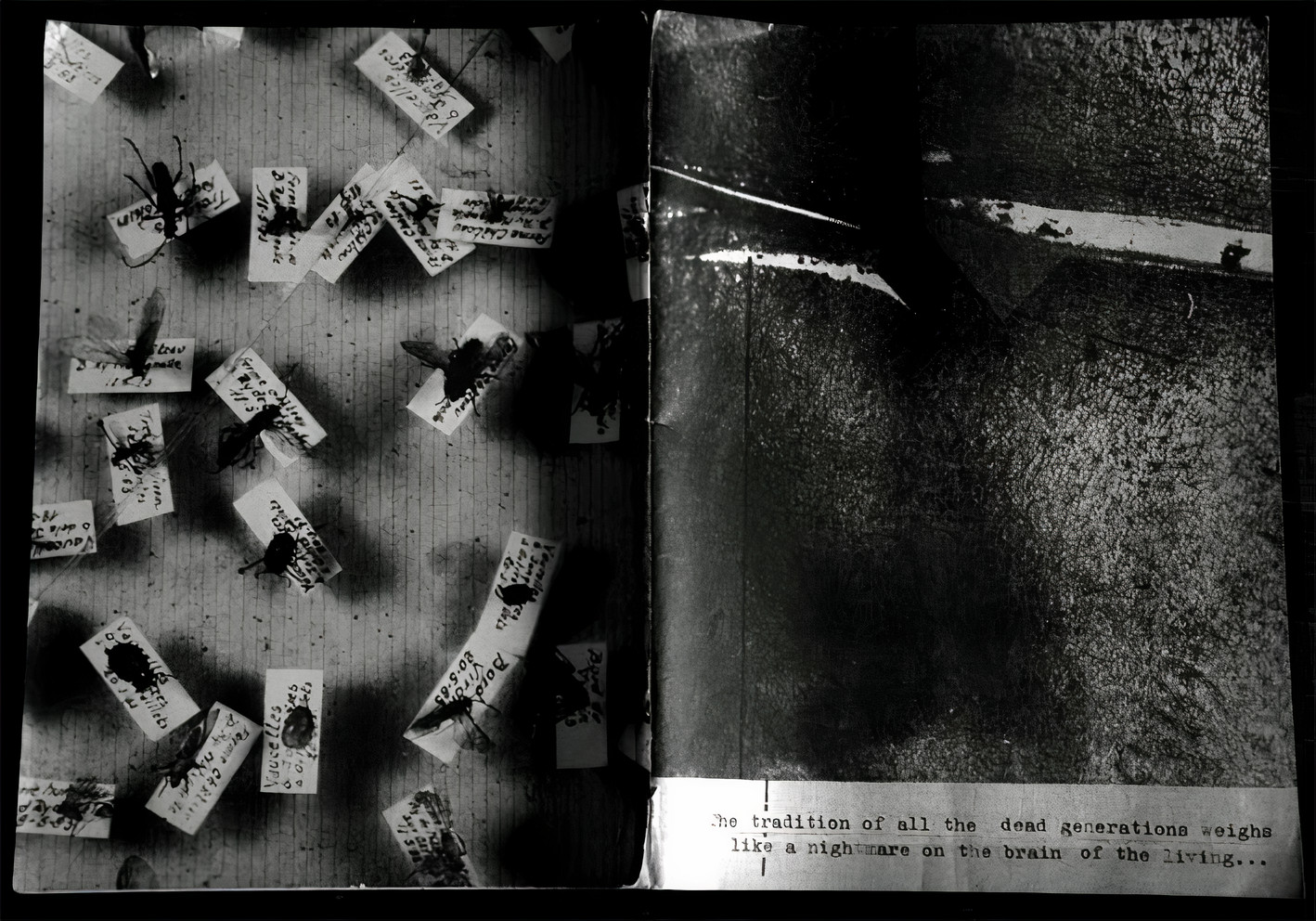

The fourth installment of a series that saw the light of day in 1997 in Cape Town, “Memorias Intimas Marcas” is an exhibition that continues to evolve, with each incarnation offering different works, artists, and modes of presentation. Starting with concepts such as amnesia and autopsy, the project as a whole aims to analyze the artistic responses to the war and violence linked to the history of South Africa, but also to similar events in Africa and elsewhere. The outcome of a dialogue among artists, the exhibition is at once marked by the violence of lived experiences, tombs, deformed bodies, and barbed wire are among its salient signs and by a complex formalization that places this work in a contemporary aesthetic discourse. On the cover of Marcas News Europe 4, published on the occasion of the show at MUKHA, we read, “The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.” The tone is set. Far from capitalizing on cultural authenticity or compassion, the exhibition explores the encounter between a specific political and historical reality and its inscription in the context of contemporary art.

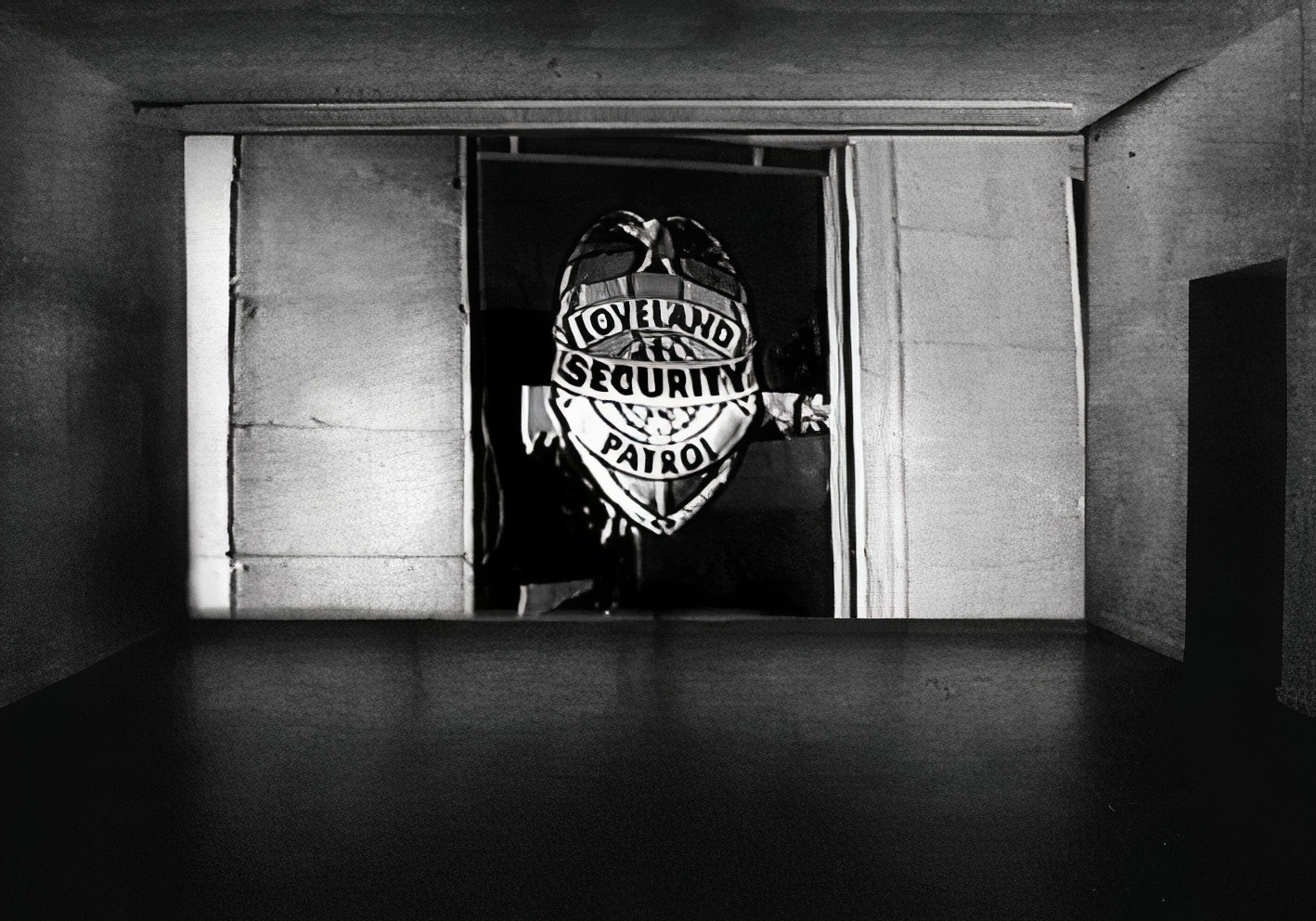

Kendell Geers, for instance, has juxtaposed Self-Portrait, 1995, the broken neck of a Heineken bottle (a Dutch export) with an enormous barrier of barbed wire, behind which a black wall bears the inscription of a war story (T.W [Exported]. As direct as possible, Geers’s installations are so many high-speed metaphors whose fearsome efficacy is tinged with an assumed craftiness. Gast Bouschet’s film, Listen to your holes, 1999, sets images of military camps against those of civilian constructions. Apparently shot in secret from a moving car, the video seems to be utterly inhabited by military secrets, an imminent and underlying danger. A work that is unsettling and paranoid, yet funny in its confusion between normality and a state of siege, Listen to your holes is both a part of the exhibition and a commentary on it.

The sculptures of Fernando Alvim, one of the three artists who initiated the project, are omnipresent, but along with the installations of Jan van de Merwe, Aime Ntakiyica, and Abrie Fourie, they constitute weak points in the exhibition. For example, Alvim’s misshapen dolls floating in aquariums full of formaldehyde (Difumbe, 1997-98) evoke the horror of scientific torture but, echoing Hans Bellmer and Damien Hirst, struggle to emerge from their references in order to signify something beyond their own monstrosity. On the other hand, Carlos Garaicoa’s architectural investigations, lightly sketched directly on the wall, intelligently combine ruins and reconstructions, tradition and modernity. New Architecture for Cuito Cuanavale, 1999, in particular, shows the delicate elevation of a “Brancusian” structure next to a hut lost in the savanna. Similarly, his video In the Summer Grasses, 1997, in which a character digs mysterious tombs beneath the sun of a desertlike terrain, manages to disturb, by turns evoking the tranquility of gardening and the morbid labor of mass burial. More monumental, Bill Bidjocka’s Explicit Paradise, 1999, is composed of a large flower bed containing a few herbs and surrounded by barbed wire and pieces of broken glass, with photographs on the walls depicting signs for home security systems. One might regret the literalness of such an installation, also found in the wheelbarrows filled with personal objects by Kay Hassan (Consecrated Objects, 2000) or in the suitcases deposited in heaps by Toma Muteba Luntumbue (U.N. Check Point, 1999) but the work has the merit of underlining the context in which the visual offerings are inscribed without preaching.

Listen to your holes [expanding/contracting]

Mexico City 1998 | Brussels 2002

En partant de la révélation de ce qu’on a appelé, en parlant du cinéaste Jean-Luc Godard, un univers dans une tasse de café, le lyrisme des choses apparemment banales se trouve ici singulièrement décuplé en parallèles qui renversent les dimensions et aspects communément admis. Tout en gardant leur propre nature, les objets, en réfléchissat des images opposées, appellent des connotations qui transforment directement dans l’image la matière en pensée.

(Francois Olivieri, 1994)

L’oeuvre de Bouschet s’organise autour de deux axes qui finissent par se rejoindre: principalement l’exploration et l’interrogation du moi, de la personne, de son parcours; à l’autre bout, l’évocation du cosmos comme espace de l’humain archétypal et de son insondable mystère.

(Anne Wauters, 1994)