Stay up to date with the latest developments in my work by following my Instagram page

24th of October 2025: I had an exciting exchange with Harper Feist about occult photography, which she published in her podcast ‘ThelemaNOW’.

You can listen to it at https://thelemanow.org/thelema-now-guest-gast-bouschet

Here is the written version:

A conversation for Thelema NOW! Crowley, Ritual & Magick. A monthly podcast by Harper Feist featuring in-depth interviews with individuals involved in mysticism, spirituality, and magic.

Gast Bouschet is a visual artist and occult philosopher. Since the 1980s, alone or in collaboration with Nadine Hilbert, he has created a complex body of work that challenges the fundamental principles underlying structure, visibility and power. His work spans a wide range of media, including photography, sound, video, painting, sculpture and writing.

Bouschet’s art has been shown internationally in numerous exhibitions (including Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw Poland; BPS22 Museum Charleroi, Belgium; Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art Porto, Portugal; Darling Foundry Montreal, Canada; Cube Space Taipei, Taiwan; Philharmonie, Luxembourg; Opderschmelz, Dudelange, Luxembourg; Muzeum Sztuki Lodz, Poland; Casino Forum d’Art Contemporain, Luxembourg; Mudam Contemporary Art Museum of Luxembourg; Busan Biennale of Contemporary Art, South-Korea; Camouflage Johannesburg, South Africa; MUHKA Antwerp, Belgium; Contretype Brussels, Belgium and CCA Glasgow, Scotland, to name a few. Together with Nadine Hilbert, he represented Luxembourg at the 53rd Venice Biennale.)

In recent years, Gast Bouschet has increasingly focused on what has been described as a primordial and uniquely blackened eco-sorcery that he practices away from the public eye in theArdennes Forest.

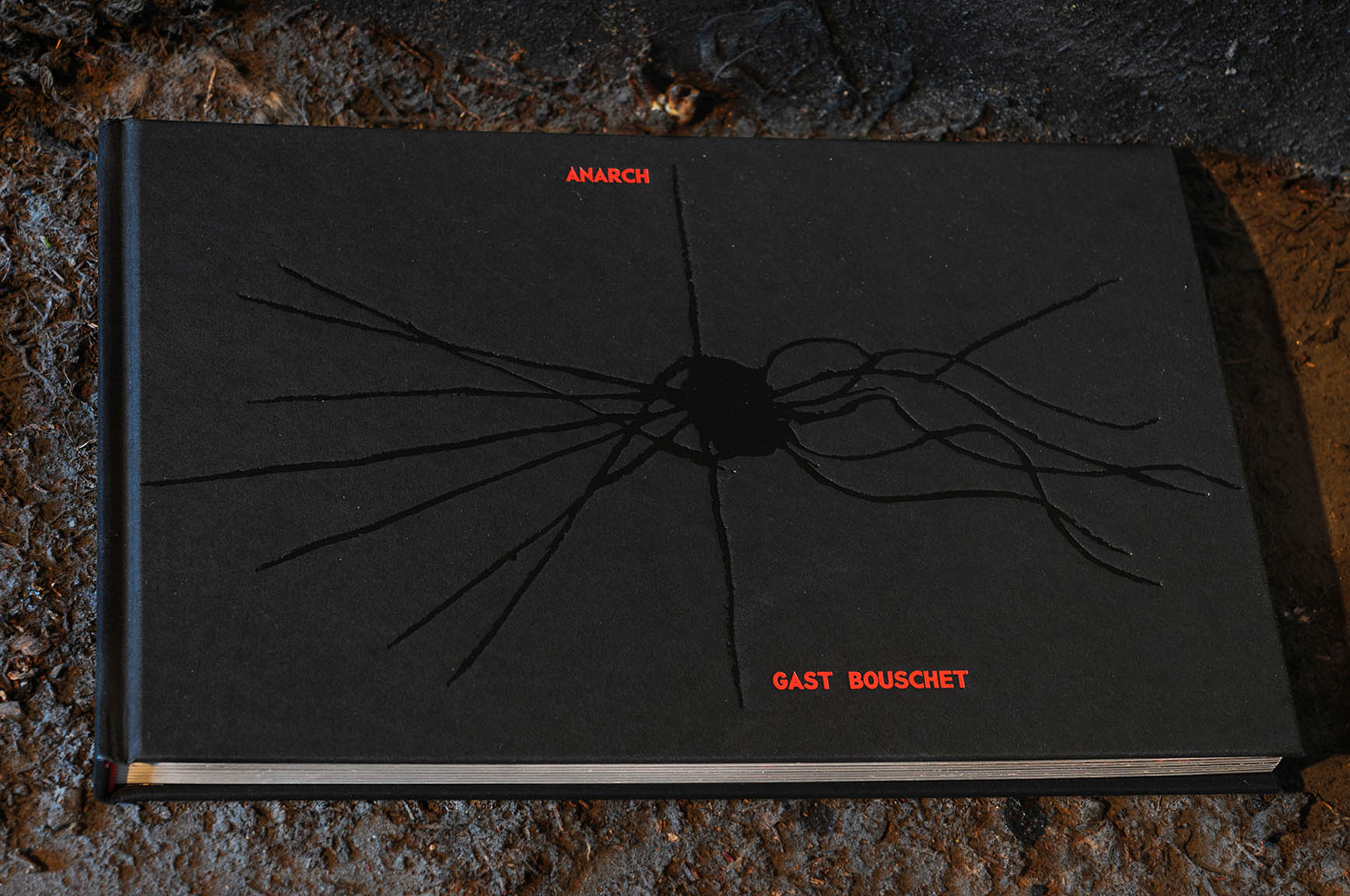

His most recent published work was Anarch, published by Scarlet Imprint in 2023. It is a masterwork.

Gast, Acher and I have been in contact via Instagram and email for several years. We recently had a long conversation about photography that I would like to share. Some of what we discussed ended up in his subsequent series of Instagram posts entitled ‘Occult Photography’.

Gast has trouble speaking due to chronic pain in his tongue, and so does most of his communication through written means. Because of that and the desire to share this material in an audio medium, Gast has given permission for me to combine parts of our chat with his written work on occult photography and have Frater Acher read his words. Thanks so much to you, Gast, for letting us make your words, your sorcerous work and your photographer’s eye available to the ThelemaNOW audience, and thank you, Frater Acher, for being the voice of Gast Bouschet.

As this discussion started with Gast urging me to post about my ritual work more often, I will simply start with his thoughts about the post I made in part because of his encouragement:

G. Beautiful images! Deeply romantic, in the best sense of a longing for the world. Thank you for sharing them.

I am very happy to be able to make a small contribution to enabling you to share your ritual work here. Not because everything should be shared. It shouldn’t. But because it relates to what you write about, that tensions need to be created and maintained. It’s about enduring what moves us and seeing it reflected out there in the world.

As a sorcerous artist, I also think that tensions should be materialised so that we can keep them in front of us and look at them from different angles. Not to dissolve them, but to work with them.

I understand very well when you write that you feel shy to express what is sacred to you. And you’re right, it leads to judgement. These are healthy attitudes that should be preserved and preferred over those who show off their devotion. You know, I am messed up in this regard because I have been working as an artist for so long. As an artist, you always walk somewhat naked through the world. There is a lot of exhibitionism in this, but also boldness and the power to overcome fear. Fear is overrated. It may protect us sometimes, but overall, it destroys more than it preserves. And it has no place in art at all. Art has to be totally fearless!

Artistic and occult work are fundamentally opposed. Art strives for visibility, occult practices for the preservation of secrets. That, too, is a tension that cannot be resolved when we do what we do on social media.

Be that as it may, being in the world means encountering its fractures and ours. The skulls and landscapes you depict so beautifully have them too. From these fractures grows the wisdom of being part of the world.

H. This text is full of important complexity… Again, you’re helping me clarify what’s necessary, what’s helpful.

The thing that is rattling loose for me now is the way I am not an artist.

I think, at least speaking of now, I am disappearing from other’s experience into my own. It’s hard to tell my stories in a way that it didn’t used to be.

Maybe this process is like breathing and at some point I will hit the other part of the cycle? Maybe all the huge and wonderful changes of the last year have expression too energetically costly?

I am trying to access my natural rhythm here, and for a change not do what the world requests or demands… but this is really a razor’s edge.

You‘ve made this more of a question than a statement, though. When I see your posts, I smell dirt and blood, I experience a ritual within myself, put there by your work, and Sharon’s now.

How can that not now be a part of my natural rhythm? It’s a Stoppard question: how can I not be myself?

G. Our place in the world is primarily defined by our focus. Being an artist is fundamentally characterised by focus. People enjoy seeing someone who has mastered a craft to such an extent that their creations are beautiful to look at. Ultimately, however, it doesn’t matter what something looks like when you have to decide whether it is art or not. As Duchamp showed us more than a hundred years ago, it all comes down to our perception. Perhaps there is no such thing as art, only people who turn something into art through their selective view of the world. In photography, it depends on which frame we choose and how we use what the camera captures to generate an impact. I think we are an artist when we focus on being one.

Perhaps it’s time to reconsider it all, including Duchamp’s perspective. For decades, I’ve been asking myself whether something is art if nobody looks at it. Another question is whether only humans make art or if animals do too. And can the behaviour of crystals, for example, be described as artistic? Does it matter what we call it?

As a young artist, I experimented a lot with photograms, which are essentially planetary records, their deep shadows hinting at the abyss beneath the two-dimensional image. My favourite photographs are not those that make me think and reflect on what I see, but those that pull the ground from under my feet. Those that express l’appel du vide, the call of the void. The photos that matter most to me are the ones that unground us.

Photographs only become magical for me when I sense the fundamental restlessness that underlies them. To access the demonic dimension that hides in the midst of the perceptual world, one has to give up total control over the image and not discard what appears unsuccessful at first glance, but work with it.

What fascinated me about the cameraless photographs was that they revealed the perspective of things. This is what we would now call the non-human gaze in the philosophies of materiality. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, when I was working on these pieces, such a magical engagement with materiality was hardly considered in the art world, and thinking about it was far from being part of the academic mainstream as it is today.

H. I have many questions and comments… the first is the weird overlap between what you have written here and the old trope of the noble savage being concerned that his soul will be stolen if he is photographed. I don’t know that was an actual „thing,“ but I thought a lot about it as a young person. I thought about it a lot when I was first using cameras in pursuit of expression, but also again when I served as a photographic model in my twenties. Was my soul stolen? Maybe it was compromised by the urge to be photographed? The second is that because of the apparent time stoppage that occurs in photography, maybe un-incarnated beings have a special door through which to join the meat crew.

G. In relation to the fact that photography robs the soul. There is a book by Sinthujan Varatharajah: “an alle orte die hinter uns liegen” (in German only, I’m afraid) that deals with photography as a weapon of colonial subjugation. He/she writes that the use of the camera is a deliberate attempt by Europeans to assert their own humanity by subjugating other life forms. And that it helped to emphasise the central distinction of colonial modernity, which differentiated between human, sub-human and non-human. It thus became a control medium and weapon that was used against the interests of the colonised people in a similar way to the guns, bibles and maps of the Europeans. It created an order over what was perceived as wild, chaotic and threatening..

I see it as similar to the exorcism practised by the church. When the Church names the demon, it gains power over it. So if you photograph someone, you gain power over them and possess their soul. I once wrote the following about this in a text about my video installation Collision Zone: As an artist whose work relies heavily on photography and video, I can’t help but point out the dominance that these media exert, whether we consider our images politically motivated or not. No one in our technologically advanced world is innocent of the prevailing conditions. Certainly some bear greater responsibility than others, but ultimately we all play a role in the exercise of political power, consciously or not. When we turn our camera on the world, we do not depict it as it is, but take possession of it and impose our view on it. The demonic aspect inherent in the word “possession” is deliberately chosen here. We gain control over the world and make it our own. But not only photography and video do this. In general, our cultural endeavours direct the chaotic flow of life into orderly channels that we have drawn to give it direction and derive artistic and financial gain from it.

But despite all my criticism of something that ultimately springs from cultural colonialism, I still believe in the sorcerous power of art. It gives us the possibility to fundamentally change our view of the world if we fully engage with its ambiguity.

H. Photography as subjugation … thinking about that. In the beginning, I am not sure it wasn’t explorers wanting to prove their importance. Or maybe in a more pure form, wanting to share the world with others. There is a sense in which is presents only a tiny, flattened version of a perhaps vast and foreign system, but that kind of control is arguably ineffective.

From my perspective, it’s interesting and fun to try to extrapolate the missing dimensions. But that is part of my personal magical practice, I guess.

The question of control is more important now, though, than when people were dragging large format cameras around the Amazon. PsyOps is warfare and the story that gets told about a photograph completely dominates the impression people will ingest.

G. Well. I don’t doubt that individual explorers were motivated by what you describe, namely wanting to share the world with others. The problem is that they did so within a system that was and is built on exploitation and domination. The images turn the people they depict into something other than how they see themselves, into something they no longer have control over. Photos are never neutral, but are shaped by the perspective we project onto the world and people. In my opinion, they are political tools. They have the power to subjugate, and they have the power to undermine subjugating systems. But they always have power. It just depends on how we use it.

H. That is certainly true, but it could be said that we never have control over what people think of us, even if we’re face to face. And what motivations others have? We never know or control that either. We all want something from other people, even if it’s just to be recognized as another person… On the topic of photography as a political tool: There was a time in the US where indigenous people were brought to Washington like animals for display. I recognize that photography was used in place of this at times, and is in this context a better option.

It feels to me right now as if photography is one flavor of experiencing other people, a 2D image of a complex and rich 3D system. It’s only one way of making that “sampling,” and it easier to see it as an incomplete representation of an entire system than our own personal experience. However, it’s not as different as we sometimes pretend.

G. These are complex and far-reaching issues that we are addressing here. I agree with everything you write. But looking someone in the face is different from taking away their image. Varatharaja writes that being photographed was a deeply traumatic experience for many. They lived on in the photos as caricatures that developed a life of their own, detached from their bodies and the places where they lived. Something was irrevocably taken from them. And that the photos are not proof of their existence, but of their subjugation. But perhaps we should talk about how we can use photography (and our texts and art in general) as sorcerous weapons to subvert the mechanisms of subjugation. My Instagram post from today resonates with that I think.

H. That is absolutely tied to the notion that something is stolen from living people when they are photographed. I think a key aspect of this is the fact the photograph is stuck in time. This must surely (at least) account for the fact that photographs often do not look like the photographed. Can the alteration or destruction of photographs unlock beings frozen in time?

G. It would be presumptuous of me to claim that I have a definitive answer. However, I can offer some ideas that are compatible with a philosophical approach known as speculative realism. One strand of this approach is object-orientated ontology. There are aspects of it that might be helpful here. OOO emphasises the autonomy of objects. This also applies to photographs, which are objects with their own properties. From this perspective, a photograph is not just an image of something else, but an object with an independent existence. I would see the photograph as a kind of demonic superposition, consisting of the image of the person (or thing) from whom the photograph was taken (perhaps even his/her soul, or at least a partial aspect of it), which he has voluntarily allowed to be taken or has been stolen from him/her, the photographer who took the photograph and thus appropriates the power over the image and the image of whom or what was captured on it, and the photograph itself, which has an independent identity and, like all objects, has an essential reality beyond its relationships and properties. And which eludes both the depicted and the photographer and the viewer in its very nature. It seems important to emphasise this, as it draws attention to the fact that altering or destroying photographs interferes with all these aspects. It has multiple effects. So what is activated by the manipulation of photographs is not necessarily the people frozen in time; our gesture interferes with all the realities and existences involved.

H. That does make sense. The photograph, the way you’re looking at it, is a system. Each member of the system may be impacted by the destruction of the photograph in unique ways. Could we see that as ecological destruction of a swamp, maybe? The animals would have no place to live, the water no place to pool without flooding. The plants would be killed outright or swept away, maybe would die in the longer term because of lack of nutrients. But I think this is important for at least two reasons: firstly there is the release of the beings somehow contained in the photograph. This is of vital importance, we should know how to release what it is that we intentionally or unintentionally trap. The second is the way this mirrors onto more classic spirit contact. Think of the grimoire with the brass vessel for the mouthy or inconvenient spirit… how do we let him or her go? We must know how to hang up the phone gracefully when we go to talk to anyone.

G. A swamp or other ecosystem seems to me an accurate way to imagine what is going on in photographic materiality. I agree with you that we should strive to understand how to free what we hold captive. We should also strive to master the art of letting go of ghosts when they take hold of us. Honestly, I do not always succeed. Some ghosts are so persistent that they lurk in my dreams, waiting to overwhelm me when I let go of control. I forgot to mention that I distinguish between the powers that I summon to open myself up to their presence, and the ones that I try to exorcise.

H. And along that track, let’s return to the topic of photographs as political weapons… Do you think having the constant ability to alter the photos has changed this? I think for people paying attention, they are less dangerous. I also think there are not enough people paying attention.

G. If I remember correctly, it was Stalin who was the first to have people removed from photos. Or at least one of the first. When I was a young photographer, I too laboriously manipulated photos in the darkroom to use them to bring about change. Nevertheless, digital photography and now AI have given manipulation a dimension that was previously unimaginable. It has obvious political power, and I am waiting for the first truly world-changing manifestation of it. It has probably already happened without us noticing. Surely it helps to be attentive, but the possibilities for deception through images are so advanced and will continue to develop in the coming years to a point where it will no longer be possible with the naked eye to recognise ‘fakes’, if we want to call them that. That said, I agree with you that people are not attentive. If you present them with a certain situation, they will fill in the rest in a way that fits their world view and their expectations. Here’s a funny example: when Nadine and I got married many years ago, we sent out cards to invite friends for a drink. The cards showed Nadine and an unkown man sitting next to her holding an iguana (that we had met by chance and posed with for a photo). He bore a vague resemblance to me because he was also bald and had a beard similar to mine. But you couldn’t really say that he looked like me. Nevertheless, many people thought it was me because the situation in which we sent the image invited them to assume that it was me sitting next to Nadine, haha!

H. Your marriage announcement is a great example of people assuming they knew what was going on. There are several really funny instances of this sort of thing in psychological research. My favorite is the movie of the equal number of people wearing black and white t-shirts and bouncing a basketball. The subject is asked to count the number of times each team bounces the ball. While the subject is performing this task, a man in a gorilla costume wanders through the basketball court. Many people (a majority, I don’t recall well) do not see the gorilla.

But the issue of photographic fakes nowadays is, as you adroitly point out, is a whole other thing. The more critical of us must now assume that everything is faked. The assumption is not that something is probably “real,” but the exact opposite. What this will do to human thought and emotion is up for grabs.

On a humorous note, I was the first Stalin at the company I worked for upon graduation with my PhD. We had a wall of photos in our company intranet showing everyone with their title, name, and office number. The lead of atmospheric chemistry was a grumpy curmudgeon. I put his head on Nicole Kidman’s body, wearing a white sequined dress. The day after I did that, management denied ordinary employees electronic access to the Wall of Woe. I’m still proud of it.

G. On the issue of photographic fakes, what you are highlighting here is something very important, I think. Until now, we assumed that what was published had a real basis in most cases and was only ‘tricked’ in exceptional cases to mislead us or to profit from misinformation. Now it’s the other way around, and basically what is true now has to prove that it is. This leads to a completely different attitude towards images and information in the world. Thank you for this insight.

The following sections is Gast talking about occult photography, based on posts made in Instagram and illustrated with Gast’s work together with Sharon Moyal.

Occult Photography. Part One.

What I refer to as “occult photography” has been the foundation of my practice since the beginning and supports all other forms of expression I use. I have touched upon it occasionally in essays and posts, but have never delved into the ontological core of the medium. This is why I have decided to explore it in more depth. I intend to write about it from a practical perspective!

Jacques Derrida’s statement that ‘every photograph is of the sun’ becomes ‘every occult photograph is of the black sun’ in sorcerous theory and practice. Actually, my essay could end here, so essential is this insight. I therefore ask you not to rush on, but to reflect on both Derrida’s statement and its sorcerous counterpart.

Derrida’s argument about photography concerns sunlight, whose source is not visible in the image. In occult photography, however, as I conceive of it, the focus is on the darkness between the stars and the hidden radiance that emanates from it. Occult photography foreshadows the dark light that is not accessible to normal sight.

Let’s start at the beginning. The word ‘photography’ means ‘writing with light’, but we could just as easily call it ‘skiagraphy’, which means ‘writing with shadows’. It is the art of capturing Urbilder — primal images that act as gateways into the abyss of unknowing. Sharon Moyal called it ‘converting attention into gravity’ in one of our conversations.

My view of photography is shaped by mystical thinking, although I must say that this is a form of mysticism without God. The inner light I speak of is therefore not divine. However, it expresses the dark sacred. To follow my train of thought, you must venture with me into speculative territory that can only be explored to a limited extent with scientific arguments. Occult photography reveals poetic truths. However, I believe that scientific findings can complement and reinforce such findings. Think of them as bridges that will prevent us from falling into the abyss before we have even begun our real journey.

Occult Photography. Part Two.

I first came into contact with photography when I was given a Polaroid camera for my first communion, which printed black-and-white photos directly onto paper. The chemicals were part of the print itself and the negative film, which had to be separated from the positive by hand, contained a corrosive developing fluid that could cause burns if touched before it was completely dry. The danger involved both attracted and repelled me.

The film ‘The Omen’, which I saw when I was eighteen, introduced me to the demonic nature of photography. In it, a photographer captured shadows that pierced the image and hinted at the individuals’ manner of death. In addition to the film’s prophetic announcement that the Antichrist would rise from world politics, I was fascinated by demonic contamination – the sinister markings that were present in the photographs. It was unclear whether these were development errors or the result of the omen that gave the film its title. I later referred to these phenomena in my work as ‘predatory abstraction’.

My fascination with photography stems from exploring blackness, which I have always considered to be its true essence. Remember that photographic paper is white before exposure, and the image is revealed through blackness. Another important aspect of analogue photography is the reversal of negative and positive, whereby light areas appear dark and vice versa. For someone who considers the black sun to be the Holy Grail, this is fucking golden. Developing photos in the lab was a manipulative, sorcerous act for me. I worked a lot with superpositions of multiple negatives on one image, and often I only partially fixed the prints, leaving the development process incomplete and the image unstable and ‘pockmarked’ by brown stains.

Over the decades, I have spent thousands of hours alone in the darkroom. Working there has taught me that beneath the seemingly tame surface of photographic matter, there are occult forces with which one can engage. This has also sparked my interest in photograms, which offer insights into the underlying principles of the universe.

Occult Photography. Part Three.

Images of burning oil wells from the First Gulf War that were broadcast in the early 1990s inspired me to pour petrol onto photographic paper and set it alight. The flame exposed the paper, creating photograms that were often traversed by what looked like cancerous black suns. Occasionally, the pareidolia effect also led to the suggestion of threatening faces. I then combined the individual prints into large assemblages.

These cameraless photographs were a breakthrough in my understanding of the medium. I realised that fundamental processes, entities or principles express themselves in photographic images when the human urge to control the outcome fades into the background.

During those years, I was preoccupied with chaos theory which demonstrates the self-organisation of life. Exploring the chaosmos in the photograms offered a new visual perspective on the universe. I discovered that the same fundamental principles of organisation and change that apply to the macro level of the universe also apply to the micro systems I observed when photographic paper was exposed to burning petrol.

Alongside studying the inner workings of nature, I developed my thinking through images based on associations and comparisons. The visual kinship that has always been at the heart of magical thinking suggests that things that resemble each other are related and can potentially be transformed into one another. Chaos theory proved that universal connections exist. It also showed that feedback loops and repetitions can cause vibrations that bring about changes on the smallest and largest scales.

Photograms enable us to capture the perspective of things. This is now referred to as the ‘nonhuman gaze’. When I was working on these pieces in the early 1990s, the creative potential of agentic matter was not as widely discussed in the art world or academia as it is today. But we need to go beyond these realms.

Occult Photography. Part Four.

Simply put, when we look at something, light reflected from it enters the eye through the pupil (i.e. a hole) and is processed into images by the brain. Photography mimics this process, and the photos I value most remind us that light enters both the body and the camera through a black hole.

In film photography, a latent image is created in the light-sensitive emulsion and made visible through a chemical development process. From an occult perspective, this means that black light and the entities that inhabit it are captured in a layer consisting of gelatine (i.e. crushed and melted animal bones), crystals and silver salts.

In digital photography, the camera’s sensors convert light photons into electrical signals. From an occult point of view, this process converts demonic particles into charges that generate sorcerous images. AI photography is something else entirely, as it uses algorithms to generate images from data. This is outside my area of expertise, so I will not comment on it. Besides, no one knows what the future will bring in this regard.

Over the past 50 years, I have spent roughly equal amounts of time practising analogue and digital photography. Here are some thoughts that I believe apply to both.

The photographer’s alchemical task is to fix the volatile and to volatilise the fixed. Most photo theorists will agree with me on the first part of this statement. Many have pointed out that photography freezes the world into immobility. In his book Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes even claimed that photography takes life, describing photographers as ‘agents of death’. But Barthes was also aware of the magical nature of photography and tried to bring his mother’s essence back to life through the medium.

The relationship between photography, mourning and death has been extensively explored, and many associate the term ‘occult photography’ with early 20th-century ghost photography. However, my focus is on the contemporary and the redistribution of agency within the photographic process. This is ultimately a political issue.

Occult Photography. Part Five.

Whether we are politically motivated or not, whenever we take a photograph, we exercise power over what it depicts. We all play a role in the exercise of political power, whether we are aware of it or not. When we point our cameras at the world, we are not documenting reality – we take possession of it. The demonic aspect inherent in the word ‘possession’ is deliberately chosen here. We gain control over what we show and claim ownership of it. Photographs are never neutral. And they always have power.

During the colonial era, for instance, photography was a weapon used to bring order to what was perceived as wild, chaotic, and threatening. For those interested in exploring how it was used against colonised populations, I recommend reading “an alle orte die hinter uns liegen” by Sinthujan Varatharajah. Unfortunately, it has only been published in German so far. The book shows how Europeans deliberately used the camera to assert their own humanity by subjugating other life forms. Important insights, as these mechanisms are still at work today.

But despite all my criticism of photography as an instrument of domination, I believe in its revolutionary potential. By combining our creativity with that inherent in the medium itself, we can challenge the human-centred perspective and pave the way for profound change. Occult photography is also a weapon, but it draws on the power of the accidental, which undermines any unilateral claim to authority. Furthermore, the contaminating lights and shadows that constitute its sorcerous essence counteract the clean evil of aesthetic capitalism.

At the heart of photography lies the question of ownership and what is actually captured in a photograph. Several elements are superimposed: the image that the subject radiates into the world; the photographer’s appropriation of this image from their own perspective; the accidental elements and mistakes that affect the image and give it its spellbinding impact; and last but not least, the photographic materiality itself. A photograph is not merely an image of something else; it has its own ontological reality.

Occult Photography. Part Six.

My aim is not to celebrate the stillness of the photographic image. The French expression ‘sage comme une image’, meaning ‘as well-behaved as an image’, expresses what I avoid. I am not concerned with polite, detached contemplation, but with engaging with the predatory shadows that constitute the very essence of occult photography.

Don’t think of shadows as the absence of light, but as a demonic presence that spreads contagiously. When it takes hold of photographic matter, it becomes a living shadow. When it does not freeze. When it absorbs black light and does not let it rest.

Both the photographer and the photograph must crave the shadow. Shadow work is hungry work. Without hunger, there is no occult photography. And hunger is only hunger when it cannot be satiated. The photograph must not be stilled. The fixed must be volatised.

Conventional photography is an act of appropriation. There is a reason why it is said to be akin to stealing souls. Pursuing this idea from a contemporary philosophical perspective makes it clear that not only human souls are stolen. Photography takes possession of everything whose image it captures, the entire “landscape,” a term that in itself reflects the human-centred perspective.

This is where occult photography reveals its revolutionary potential. It enables us to escape the hall of mirrors that traps us in our own reflection and connect to the wider planetary system. Up to this point we are still on relatively safe academic ground covered by environmental philosophy. It is when it is put into practice that it becomes groundbreaking. When we actually become the ‘other’.

I will return to the practical aspect in my ongoing investigation of Becoming Demonic, which I’m conducting with Sharon Moyal and other sorcerous artists. For now, let me conclude this exploration of occult photography by noting that it reflects the profound crisis of perception that we are witnessing today. Drawing on the breakdown of reality in the 21st century, occult photography paves the way for a profound shift in our fundamental understanding of existence and our relationship with the world.

Gast Bouschet, 10 September 2025.

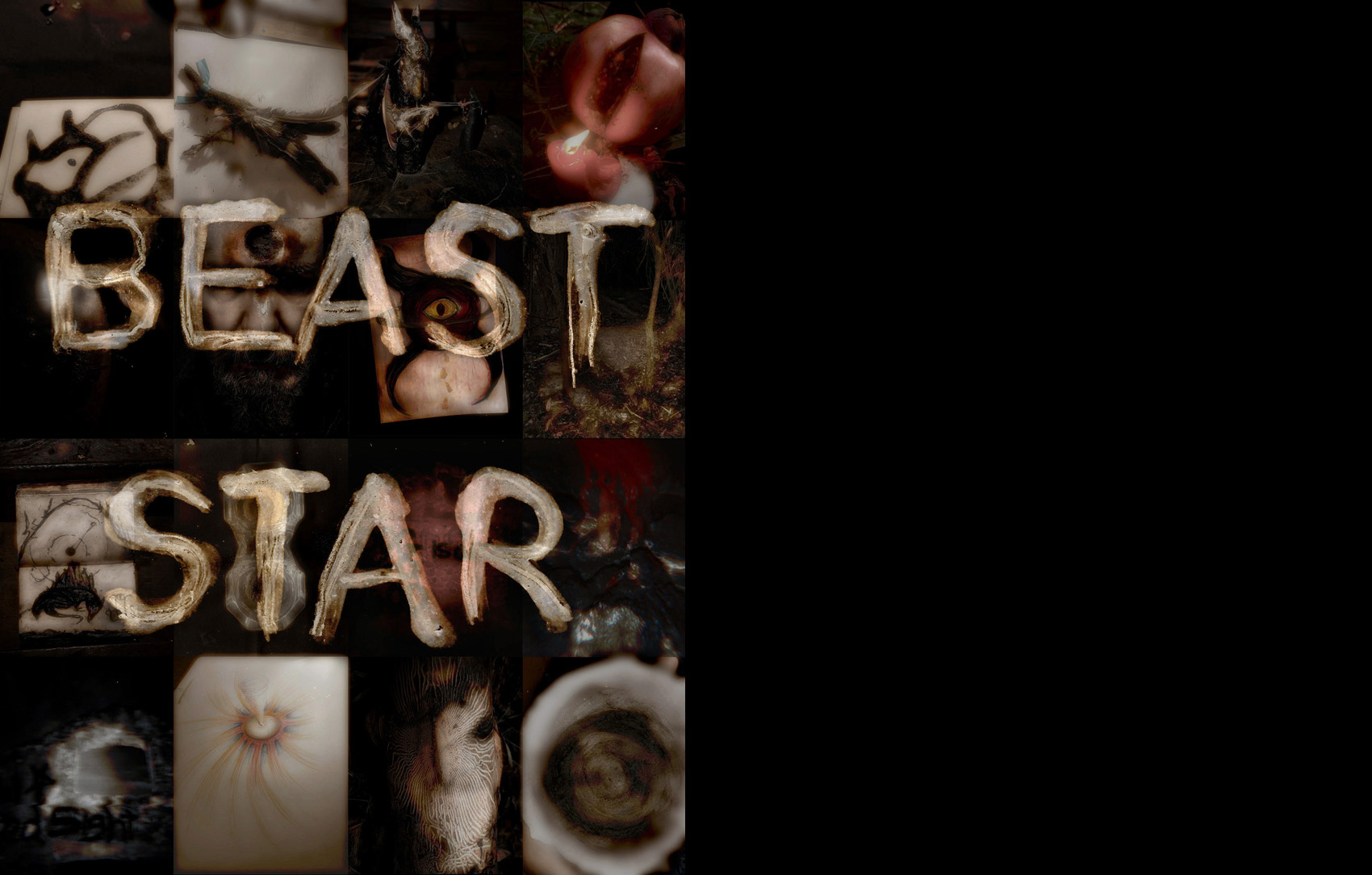

The Star and the Beast.

Visit the small archive that collects images and texts from those who took part in our rite on 29 March 2025, which aimed to follow the Star of Night into the Underworld and associate with the transformative power of the Black Dragon at work there.

Click here

Resurrection Spell. Part One.

This is a plea for an occult politics. A politics of art and sorcery that operates in the underground, which it redefines and revitalises. It’s a politics that opposes every form of authoritarian thought and action, but knows that when authoritarianism becomes the rule of law, open resistance means being crushed by it.

It is a masked politics, articulated on the border between visibility and invisibility. What distinguishes those who use it from those who take to the streets to protest is that they do not work with slogans, but with coded language and visual metaphors based on a poetics of transgression. While the first method aims to participate in the political system, the second aims to subvert it.

Occult politics is first-person politics. It’s a humble politics. Perhaps it’s even an anti-politics, a means of avoiding systemic thinking. After all, there is no system, only individuals and their fragile bonds, driven by needs and desires that are often in conflict. We should not fall prey to the naive idea that conflicts will be resolved if we are all just nice to each other. But neither should we fall into revolutionary violence, which only leads to new forms of oppression.

What is called for today are are non-violent forms of struggle. We need to develop modes of action that express the possibilities of creative change; countercurses that strike at a technological system that has taken control of our earthly existence and reduced everything to a spectacle.

Our first and most fundamental task is to ground ourselves. I can’t tell you how to do it, but I can tell you how I do it. My whole life in the Ardennes Forest revolves around grounding. It involves recognising that we live in an animal body that gives birth and dies. As I’ve described in my recent posts, working with the blood left over from the slaughter of a goat or devoutly observing the birth of a kid in a barn helps me to contemplate the visceral realities of existence. Such confrontation allows for a more authentic experience than that which enters our consciousness through screens. It is also the prerequisite to develop sorcerous agency.

Resurrection Spell. Part Two.

Building on the aforementioned grounding, we will see what needs to be fought, what is worth preserving and repairing, what can be left behind as caput mortuum and what will be reborn from the blackness or ashes that are synonyms in some traditions. The art that emerges from such an awareness, and this is what I am concerned with, will be a new kind of Arte Povera that is intensely political in that it undermines imperial and anthropocentric fantasies of grandeur.

Since I know how uncertain many artists are about whether it makes sense to see their work as a revolutionary practice, my point is that art can do something when it escapes systemic control and turns that escape into an act of sorcery. Sorcerous art is an effective means of summoning what I call ‘bestial freedom’, liberation from ideological entrapment. It also allows us to honour nature in all its dark, uncompromising power and beauty, and thus to resist the manipulative forces that currently poison world politics, promising paradise and delivering hell.

What we all have in common in these uncertain times is the need to unearth ancient resilience and strengthen our survival skills. Fear must not paralyse us, and we must overcome cynicism and world-weariness and bravely face whatever life throws at us. The threats are many and may require unprecedented efforts. It may be that the path humanity has taken will lead to a global catastrophe, but even if this is the case, it is unlikely that things will simply cease to exist. If we are to have any chance of sustainable change, we need to break out of the vicious circle of anthropocentric error and develop a bio-ontology that enables a politics that considers the planet as a whole.

I suggest we use the conjunction of the Sun and Saturn this spring, which signals Saturn’s death, or rather its escape into the unmanifest. Saturnian alchemy teaches us that change cannot happen without destroying the old state of existence. So let’s follow the cosmic call and go even deeper underground to sow the seeds of transmutation. The sun of night ignites a future that will flourish and reach beyond what we expect of it today.

Note. Many thanks to Sharon Moyal who gave me valuable input for writing the last part of this post. Since last year, we’ve had exciting exchanges about the blackness of Saturn and its relationship to the Sun.

Gast Bouschet, 21st of March 2025.

Path of the Goat. Part One.

The ritual work involves a goat skull I found down by the stream. A place where dead animals are often dumped. By poachers, but also by people getting rid of farm animals. Through my work I often try to give them back some kind of dark dignity in death. But what I am showing here is also about sorcerous empowerment and blood as a vehicle for life.

First I rubbed the skull with ashes I had kept from a bonfire I had made at the winter solstice. Then I placed it on my shrine in the forest shed and meditated on life and death as part of a continuous cycle at the beginning and end of each night for two weeks. On the first night of the new lunar year, I poured blood over the skull, which came from the slaughter of a goat that a friend had done on her farm. The meat, as with all slaughtered animals, was intended for human consumption and she gave me the blood for my ritual work. It had coagulated surprisingly quickly and became clumpy, so I had to stir it to make it flow and initiate a symbolic rebirth.

The aim was to transfer the animal soul carried by the blood to the skull as well as to the totemic sculpture that plays a central role in my practice. It may be worth mentioning here that in indigenous cultures what we call a totem is often seen as flesh or congealed blood. Ontologically, the rite is about kinship, about sharing a common mass of blood with all the creatures that carry it. I see human and other animals connected by this vital substance, as if we were part of one mighty beast that embodies nature, and the act performed serves to consolidate and strengthen this relationship.

Then, in a moment of visceral communion with the predatory forces of the universe, I drew an image that is a variation on Goya’s painting of Saturn. As I interpret it, it is not a portrait of a cruel patriarch tearing his sons apart for fear that they might overthrow him. Rather, it expresses the embodiment of the force that devours what it has given birth to. So I didn’t draw Saturn’s head as fully human, but as a goat-like hybrid, a fierce embodiment of nature.

Path of the Goat. Part Two.

‘Immerse yourself into yourself, since you carry it with you, just like the salt and its volcano.’

The Stone of the Wise is animal-like, akin to our blood. Working with the liqueur vitæ is therefore a potent means of spiralling us back to the animal soul that continues to dream within us. It frees us from human-centred, abstract reasoning and enables us to participate in the image-creating power of the earth.

Participation in animality opens up the possibility of overcoming the all-too-human in Nietzsche’s sense and understanding ourselves as part of the fluidum of life. This approach is a prerequisite for the development of a biocentric politics that fundamentally questions our role on the planet and suggests a way out of the impasse our civilisation has reached.

From a sorcerous and alchemical point of view, however, opening up to animality is only an intermediate step on the way to the wilderness of the universe. What we know about the universe gives us no insight into the meaning and purpose of life. We do not know where it came from or where it is going. All we can surmise is that the process of creation is inextricably linked to the process of destruction. And vice versa. As artists, therefore, we welcome the process of destroying what we have created to make way for new creativity and freedom.

In what I am showing here, this is expressed by burning the drawing and mixing its ashes with fresh goat’s blood. Alchemical sorcery aims at the regenerative metamorphosis of Saturn’s black lead, that which remains in the crater of the dormant volcano. In this piece it is the ashes, revived by the blood of the slaughtered kid, that I collect in the sacrificial bowl and throw to the rising sun.

‘Our stone has two natures, so it must be fed by a goat that gives both milk and blood.’

In this rite I mix milk (mercury or fat menstruum) and blood (sulphur or fiery plasma) in the offering bowl. Unlike the Christian-influenced alchemy that flourished in Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, our sorcerous version of it does not strive for a harmonious union under the Law of One. Instead, it combines the substances in such a way that they do not completely dissolve into one another and cancel each other out. They overlap and form complex patterns reminiscent of the formation of primordial galaxies (see Photo 1). And their chaotic interactions give rise to topographies whose boundaries remain controversial. At first glance, it looks like mixing oil and water. But in the heterogeneous embrace, the substances impregnate each other, ushering in the birth of the monstrous but true child.

Path of the Goat. Part Four.

Triumphant Birth.

Behold the sacred kid, blackened by prayer.

Path of the Goat. Part Five.

Ours is the path of the goat. The path of those who jump from one precipice to the next without losing sight of their goal. Those who enter the underworld through the narrow gate at the crossroads. Those who fertilise the black egg in the coffin and gestate it in the witch’s womb. Those who nurture the growth of the monstrous but true child. Those who sign the pact with blood and realise liberation in the moment of struggle. Those who know that freedom is never secure and cannot be possessed.

Gast Bouschet, 3rd of March 2025.

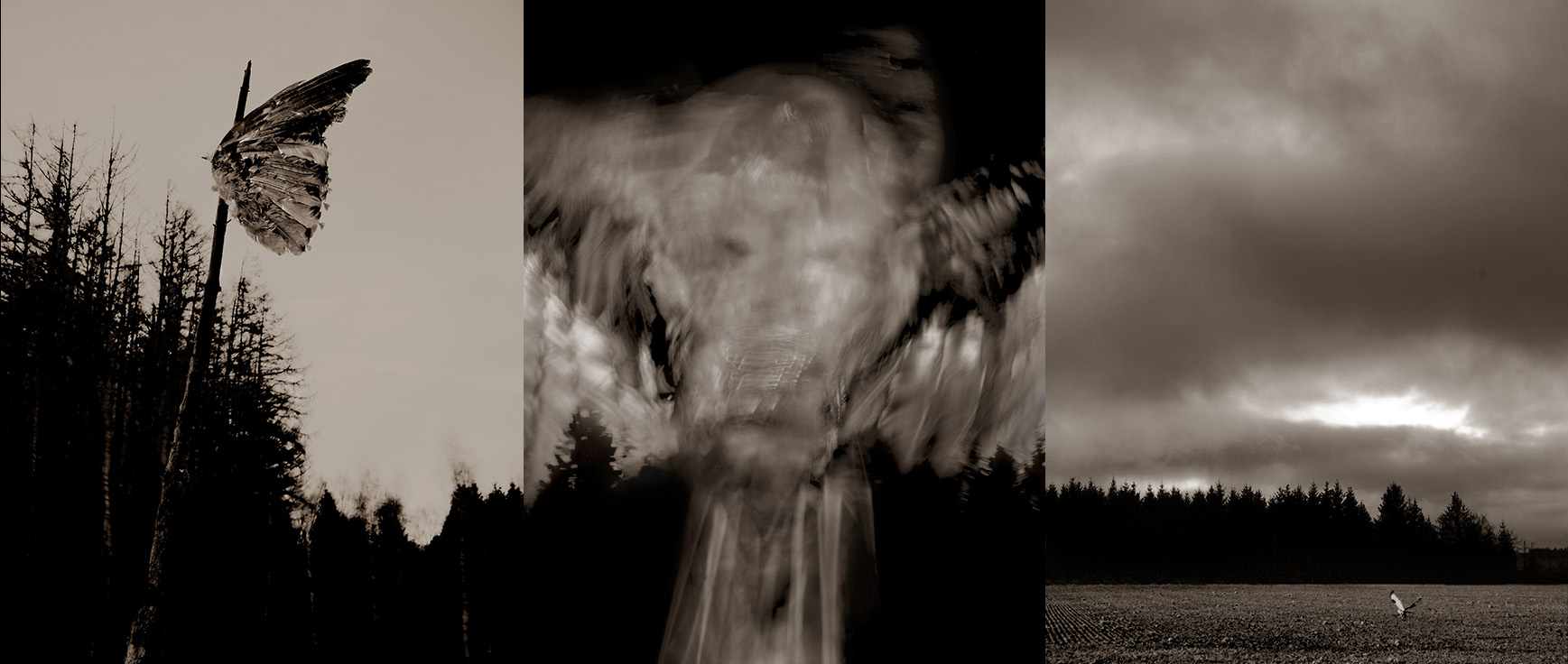

A Dark Shamanic Practice for Dark Ecological Times.

This short five-part survey of contemporary shamanic art looks at interaction rituals, particularly in relation to the birds of the Ardennes, a third of which are currently threatened with extinction and the situation continues to deteriorate. I will explore whether contemporary art that emerges from a creative encounter across species boundaries can be labelled ‘shamanic’ in a European context and what purpose it can fulfil.

Part One.

The production of an artefact like the one shown here takes a considerable amount of time and involves several steps. The first involved closely observing the scavengers as they ate the head and paws of a chicken that had just been slaughtered by friends on a neighbouring farm. This process was essential for establishing a deep connection with the base matter underlying the sculptural work.

After this outer and inner nigredo, I created something new by fusing the remains of the farm bird with those of a dead crow (i.e. a wild bird) and other materia magica. The resulting sculpture in some ways resembles what is called an ‘empowered cadaver’ in African Vodun, although I took it more literally than what is usually involved in the making of bocios, as Vodun sculptures are called. But I see this piece as primarily European, or even specific to the Ardennes, as it is linked to local economies and ecosystems and draws its strength from birds that have lived and died here.

Whatever the term ‘shamanism’ means exactly, now that it has moved away from its Siberian roots, if we want to apply it to our work, it must take into account our current living conditions. We do not live in an unspoilt wilderness, but in damaged ecosystems, and our so-called power animals are dependent on human regulation and threatened with extinction. I am sceptical that what has been damaged can be healed as long as the human population and its consumption continue to grow. And I shudder at the grim prediction that human activity may one day leave chickens the only birds on Earth. Still, I think shamanic art can play a role in our times by empowering the soul to transgress ecological grief and fear, and by building new connections between inner and outer nature.

Part Two.

The ritual wearing of a mask is less about hiding one’s appearance or being seen as someone else, and more about seeing through the eyes of the other. This alone justifies a contemporary shamanic practice, as it journeys us out of the human perspective. In our everyday busyness, we forget that there are as many views of the world as there are species or even animal persons.

Wearing the mask overlays our human nature with our animal nature and merges the two into a unified consciousness. As a result, we see the surroundings with different eyes, in my case the Ardennes forest and its edges, which provide ideal hunting grounds for the resident birds of prey. From such an ecstatic superimposition of realities arises the possibility of developing a lasting sense of intimacy, both with the animals that live with us and with our own animal-ness, which allows us to enter into a kinship with them, as tribal cultures do by making animals, often birds, their totem.

To animate a mask, it is useful to smear its inside with animal and human blood. This facilitates both the mutual attraction and the lighting of the inner fire that we need for the ritual work. It is a perilous affair* for more than one reason and requires an art that has little in common with what we normally associate with the art we see in museums and galleries. Most of the art exhibited there leaves us stuck on its aesthetic surface. Shamanic art is not what we understand by ‘fine art’. Its purpose is not to please the eye through masterful drawing techniques or the ability to create exquisite objects. Rather, it draws its power from the formative and destructive processes of nature, channelling them so that they invade images and sculptures and then, through their contemplation and handling, enter the mind, where they effect change.

* Coincidence or not, many years ago a fire broke out one night after some ritual work with a mask and I woke up the next morning in a toxic cloud that left me coughing up black phlegm for days. I’ve been careful ever since.

Part Three.

The ritual tool shown here, which I carved and then painted with buzzard excrement, initiated the flight to the nadir of the year. Spiderwebs hang from it to bind the demonic forces that accompany the journey into the underworld, both that of the forest and our own, to retrieve our animal soul trapped deep within. The confrontation with our own animality is characterised by ambivalence, because we only possess it if it also possesses us. Nevertheless, it is essential if we want to lead an authentic occult life.

Since Darwin’s study of human evolution, we know that we have been animals much longer than humans. However, we cannot commune with our animal ancestors, who are still buried in our bodies, through scientific means. Rather, this requires what Eliade called ‘archaic techniques of ecstasy’. And this is where the manipulation of sacred objects comes into play, as they enable the exchange of power and the transfer of transformative energy between our human and animal natures. In such borderline experiences, the mind shifts from a verbal to a visual level, so that we think with images, which is essential both for making sense of the visions we encounter on our infernal journeys and for creating this kind of art.

The key to visual thinking lies in association, juxtaposition and superposition. Shamanic thinking is characterised by the fact that the more similar things are, the more interchangeable they are. And if we can put them in a state of excitement and make them resonate with each other, we can transform one into the other. Shamanic kinship is not defined by the biochemical compositions that science uses to categorise the natural world, but by mutual attraction.

Engaging with our nonhuman otherness in an embodied sense and opening our bodies, or rather being opened by the other, results in the loss of our stable identity. However, this process allows for intimate relationships. Making shamanic art is like making love: it touches the deepest part of us, expands our sense of self and enables the transmission of emotions between those who participate in it.

Part Four.

Totemic wooden objects retain a connection to the forest from which they come. They carry the memory of the mother trees that pass on their heritage, of the drought of exceptionally warm summers that threatened their survival, of the sap that flows to the roots in autumn, of their interaction with the mycelium, of the soil that holds the trees in place, of the minerals that nourish the soil. They also carry the geological memory of the ground and the catastrophic events that have shaped and traumatised it, the stored experiences of the microbial, plant and animal life that has walked on that ground, the birds that perched on their branches, the air that has carried them and the storm that has raged through the canopy. All this makes up the forestial memory and that of the sculptures created from it.

Sometimes I work the wood more or less. In the case of the piece shown here, which occupies a central place in my shrine, it has hardly been worked at all. I think the less a totem deviates from its original appearance as a tree, the more it acts as its mediator. And of course I don’t seal a wooden sculpture so as not to silence its oracular voice.

Perhaps the daily communication and touching of the shrine, which carries the essence of forest, contributes to what Lévy-Bruhl called ‘participation mystique’. The intense relationship with a sacred object that allows it to be experienced as a complex form of life in itself. I could warm-up to that idea if we could free it from its paternalistic view of the ‘primitive psyche’. But we would probably be better off focussing on what lies ahead.

What matters today is the development of a way of thinking and feeling in which human subjectivity is a part, but not the dominant principle. My ritual work is in many ways about breaking chains, those of Anarch*, entrapped beneath the world system, but also the ideological chains that keep us trapped in the belief that human nature is separate from nature as such. Ultimately, it is about revealing our most authentic inner being and creating new forms of solidarity and a shared politics of the earth.

*As readers of my book of the same name, published by Scarlet Imprint, will know, working with Anarch is a central concern of mine. Not only, but also because of the paradox that Milton introduced into the term in ‘Paradise Lost’ when he combined ‘monarch’ with ‘anarchy’. He was expressing the fusion of the natural kingdom with its underlying principle of chaos. Nature is anarchic and yet organised. But it is a horizontal organisation in which no power is exercised from above. The artworks shown here feed on the primordial dark sacredness of matter, the pagan graininess embodied in mythological tales as the ancient gods who were defeated and banished to the underworld by monotheistic religions and later by modernity. They must endure chained there until the fabric of the world realigns in such a way that they can be freed by the sorcerous intervention of their accomplices on earth and regain their original power over world events. In such a revolutionary narrative, the activities of sorcerers and shamanic practitioners overlap, which is rare, as the shaman is usually seen as the sorcerer’s opponent in traditional animistic societies. In this case, however, they are not working against each other, as both practices aim to rid the world of its current ills.

Part Five.

Contemporary shamanic art enables liminal experiences in the undead landscapes of what has recently been called the anthropo-obscene. We should not be afraid to call this black shamanism, for it expresses the poisoning of the planet and the extinction of a multitude of species, perhaps including our own. Our shamanic task is to merge the horror with the wonder, and to transmute the

poison into an elixir that leads us to radically reinvent our selves and our role on earth.

I don’t presume to prescribe any particular way of doing this, but I also don’t want to hide what I think is desirable. Take it for what it is: an experience-driven approach to dealing with the mess we’ve gotten ourselves into. I am not saying that what I am proposing will save us, but it will prevent us from drowning in the shame of giving up without trying to embody change.

Let’s build the dream of an interspecies community based on ecological equality. Let’s challenge the rules that maintain hierarchies, even between species. Such work will make us outsiders, but shamanic practitioners have always impacted their cultures from the margins. The question is whether our culture recognises the need for visionary practices that inspire bold political action. And whether we will be able to draw strength and ancient resilience from adversity. If we want art to be part of the solution and not part of the problem, we need to free it from its entanglement with capital and build our own cultural ecosystem based on a passionate engagement with nature, no matter how damaged or hostile it is or will become.

Let’s fight the cancer of the human soul with assault sorcery. Let’s practice mystical anarchism, a mysticism without a divine ruler. Let’s journey into realms where we experience our innermost self as that which is primal and darkly sacred. From such a deep connection, a new identity will emerge that is no longer just that of homo sapiens, but embodies multiple natures simultaneously. Well then, soul, take flight with the birds and heal. Who would have thought that my black shamanic story would become a healing story after all?

Gast Bouschet, 14th January 2025.

Video accompanying the lecture of Peter Mark Adams on Gast Bouschet’s book Anarch, published in collaboration with Scarlet Imprint, at the Metamorphosis – Ecstasies of Matter & Image conference at the University of Copenhagen on 31 May 2024.

Text by Gast Bouschet

Selected & narrated by Peter Mark Adams

Produced by Darragh Mason

Sound. P:R:I:S:M by Sutekh Hexen & Funerary Call

Many thanks to the University of Copenhagen for hosting the event, to Kevin Gan Yuen for the permission to use the music as a soundtrack and to Alkistis Dimech & Peter Grey of Scarlet Imprint for providing the images for the slideshow.

Since the publication of Anarch, I’ve started a new body of work that you can follow on Instagram

INTERVIEW

I had an enriching exchange of ideas with Snappy and Graham, the hosts of the podcast Searching for Dragons, about the politics and poetics of my sorcerous art.

They present our collaboration with these words: “We previously discussed Gast Bouschet’s book Anarch on the fifth episode of our podcast, Searching for Dragons. After this discussion we began a friendly dialogue with Gast talking about sorcery and philosophy, and sharing perspectives. This was a fruitful and beautiful discussion and we felt it would make for an incredible interview. Due to personal health issues, Gast was unable to do a live discussion so instead Graham and I wrote several deep questions for Gast to answer in text. You will find the full text of our interview below.” — Snappy of Drawing Down the Stars

Here is the link to the YouTube episode “Searching for Dragons”, in which Graham and Snappy discuss the interview on 16 December at 8pm EST : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqlpe9HAHlM

You can watch the episode of Searching for Dragons where they discuss my book Anarch at the bottom of this page.

Please visit https://medium.com/@drawingdownthestars/interview-with-gast-bouschet-author-of-anarch-fb91b68a6abd

Drawing Down the Stars is a magical and sorcerous collective focused on creating discussion and videos about Magic, Mythology, Occultism and Witchcraft.

Here’s the full interview:

How did you become engaged in Occultism and what drew you initially to alchemical practice? And what separates your work from classical alchemy?

Well, there was something like an initiation experience. When I was 9 years old and my grandfather, who had died the day before, was laid out in the neighbouring bedroom, I had a nightmare from which I woke up brutally when a black stone lying on my chest suddenly began to pulsate with flashes of light and then fell into me, pulling me into an inner black hole. That night drenched in dread, and the strict Catholic mourning rituals my family went through for a year took their toll on me, and I almost didn’t grow for the next three years. A decade later, I realised that I had dreamt of what is called the Black Sun in alchemy. The first image of it is probably printed in the treatise Philosophia Reformata, which I also had tattooed on my body so that I would carry it with me as a living sigil until my death. When I was in my early twenties, I went on many LSD trips, which brought back what I had experienced as a child and sometimes dragged me even deeper into this abyss. Horror and ecstatic joy are very close to each other with this drug and sometimes even merge at high doses. In smaller doses, LSD enabled me to experience my physical access to the world in a completely new way. At the time, I saw Castaneda’s first three books as a guide to the life of a sorcerous warrior who always has death an arm’s length behind them and who must pass tests by going beyond what is generally considered possible. Having previously been involved in sports at a fairly high level for ten years, including being a national champion in judo in my age group, doing high jump and long jump, and playing handball in the junior national team, I was in good shape in my twenties and had mastered tasks on LSD, such as quickly crossing a stream by jumping from wet stone to wet stone at great speed. Or I would go hiking in the forest at night, sometimes in difficult weather conditions and in complete darkness, to face the blackness and encounter the demons living there. With or without drugs, I put myself in a state of mind that, with a little good will, could be compared to that of a sorcerous warrior. Such a view of course romanticises what I was doing and what I was capable of, and I was very lucky not to break my neck, but it was incredibly empowering at the time to physically do things that I then saw as necessary steps on the path of sorcery. After those wild youthful years, I became more cautious, but the physical approach remained throughout my life until I had an accident in 2017 that put an end to it, or at least redefined my physical connection to the world. I had often shot my videos in harsh conditions, working in toxic fumes on volcanoes, climbing into caves or crawling under glacier tongues where sometimes heavy chunks of ice would break out next to me and could have killed me. Danger and seeking out demonic forces in the wilderness have always been an essential part of my work, and I have done my best to convey this in the images themselves. Without it, I don’t think it would be possible to make sorcerous art, which always has to pose a threat to be labelled as such.

Classical alchemy is a vague term, as alchemy was practised on different continents at different times and there is no standardised definition for it. There are practices that are summarised under this term, but they can only be compared with each other to a limited extent. Be that as it may, I am trying to update alchemical thinking and practice for our century, which is characterised by an unprecedented relationship with nature, a nature that we have changed so much that it has little in common with what can be called natural. But nature is a problematic concept in itself, because it is characterised by our view of the planet, which actually says more about the people who look at the world than about the world itself, and which really only refers to the fungal infestation that covers the planet’s crust, as Schopenhauer once put it. In any case, what we can call fungal infestation has been significantly altered by us in a kind of black magic that poisons our living conditions and those of the other beings with whom we share the planet. I associate this planetary poisoning with the personal suffering that manifests itself in the chronic pain and disability that plagues my body. So there is a kind of inner and outer alchemy at work in my art. But actually, the toxic black alchemy I am talking about here is only one aspect of what I understand by the dark sacred. At the centre of my work is the primordial blackness that is the womb and tomb and chaotic seed of all possibilities. And it is important for me to emphasise that this blackness is everpresent and was not only there in the beginning. Blackness is the living substance of the universe, which is active in both the infinitely large and the quantum small. My art is about nourishing this blackness and channelling its creative potential into my artworks. Only when I succeed in this can I speak of my art as black alchemy or alchemical sorcery.

You mention in your book the works of Georges Bataille, what are your thoughts on his concept of immanence and humanity’s inability to return to a past of continuity, one free of disconnection?

From a sorcerous point of view, it is important that we penetrate the deeper layers of being through visionary work, which also means a regression in time, to the primal human and beyond into the animal and even bacterial and microbial, to finally end up in the black primordial matter. Bataille’s satanic conception of base matter, which opposes the betrayal of nature committed by the Christian religion in which I grew up, is important to me. I see in his base materialism the continuity you mention, Nietzsche’s “Ur-Eine” or primordial oneness, which I locate in the chaotic depths of the chthonic universe. The encounter with base matter is like falling into an abyss.

In the context of black alchemy, Bataille’s idea that matter is an active principle, especially in its decomposition, also seems important to me: “At the moment of metabolic meltdown all the daemonic, cosmogenetic force contained in the flesh is discharged in a dialectical expenditure that reworlds the world.” The idea of reworlding the world has made a lasting impression on me.

Bataille also explored the art of transmuting fear and pain into joy, at least temporarily, which has always appealed to me because of my experiences as a young man and which has taken on a much greater significance since my accident after having to live with chronic pain. It’s not about being lulled into false hope – hope can be a terrible enemy when you can’t permanently change a condition for the better – but about going into the depths of pain and fear and standing in what he calls a solitary darkness , in an attitude without the gesture of a supplicant. This « attitude without the gesture of a supplicant » is that of the sorcerous warrior that I have been striving for since my youth.

If you will allow me, I would like to conclude the question on Bataille with a quotation from him: “I myself stand on various peaks that I have climbed sadly; my various nights of terror collide – they multiply, they intertwine and these peaks, these nights . . unspeakable joy… I pause. I am? a cry-thrown back, I collapse.”

Your work is titled Anarch, and there are references to Milton’s Paradise Lost. Can you talk about your thoughts on philosophical Anarchism and the concept of the Anarch and its relation to Saturn?

Milton is perhaps the closest to my sorcerous idea of chaos in that on the one hand he addresses the anonymity and multiplicity of embryon atoms that are constantly fighting for survival within the eternal anarchy of chaos, and on the other embodies this chaos in the paradoxical figure of Anarch old, which is helpful when working magically to give a face, so to speak, to the power we are dealing with. I don’t know if I would describe myself as an anarchist in the historical sense. I am cautious when it comes to collective struggle for common goals. I think that basically only individual existences are real, communities of whatever kind are illusions that are also mostly ideological. But perhaps this is the true anarchism. Bakunin pointed out that political anarchism rises out of our animal essence. In any case, my thinking can be described as anarchistic, in the sense that I believe that the universe itself is chaotic or anarchistic, and I reject any form of hierarchy in the exercise of power, as far as this is possible in relation to all living beings, but of course this is doomed to failure. I fight viruses and bacteria with drugs like everyone else when they make me sick and threaten my life, and I feed on animals and plants. We live in a predatory universe in which survival can only be guaranteed if beings kill other beings. We have to live with this existential guilt that we humans are part of the collective murder without lying to ourselves by reassuring each other that we are on the right side of the divide between good and evil. The virus is not evil, it fights for survival, although the status of viruses is not clearly defined and they are thought to exist somewhere between death and life, an intriguing idea that would be worth exploring further, but never mind. Viruses try to survive in some ways, just as we do, but I’m not telling you anything new here.

The leap from Anarch to Saturn is a bold one, but let me try. I think that behind the figure of the mythological Saturn is chaos. However, I’m not sure I would go so far as to call Saturn himself an embodiment of this chaos as we do with Anarch. Saturn is often referred to as the guardian of the threshold between the known and the unknown universe, which is probably due to the fact that the planet whose name it bears is the last one we could see with our eyes before the telescope was used to observe the night sky. But the figure of Saturn appears in many mythologies, European, Arabic, Jewish, Indian and probably some more, and I don’t want to reduce it to one meaning. To a certain extent, I also find the vision of the planet Saturn from the point of view of the Fraternitas Saturni exciting because, as with the black sun, it involves the alchemical marriage between light and blackness. They see Lucifer who embodies the light as the higher octave of the planet Saturn and Satan, who embodies darkness, as its lower octave.

Throughout your work there is a rejection of western “spirituality” and there’s a professed hard materialism. Can you discuss your perspective on spirituality and materialism?

To put it in a nutshell. I think that matter is everything that exists, but that it is so mysterious that it has little in common with what we generally understand it to be. The spiritual takes us away from what we call nature and brings into play the transcendental, which is somewhere beyond earth, usually in heaven. I can’t relate to the concept of the spiritual, it’s too airy and not earthy enough for me. I’m too much of a Nietzschean who whispered to me that I should stay true to the earth.

I think we in the West gave up something essential when we elevated ourselves from the animistic substratum to the transcendent. It is unfortunately very ambiguous to speak of animism today because the term is tainted by the colonial thinking that still characterises us today, but I cannot think of a better term at the moment that would more accurately describe what I mean, so I use it with the caution I emphasise here. In the case of my practice, I should also call this animism sinister animism, because as I have already mentioned, we are dealing with a world in which the natural of nature has been destroyed, though probably not yet to the point where the earth can no longer exist. The question that arises is the one that you, Snappy, raised in one of our earlier conversations. Namely, whether humanity will survive this great change. I will leave that question open.

Can you discuss your connection to African traditions? Your perspective on Vodun and animism in general?

These connections are based on personal experience. I need to expand a little to shed some light on the context. I have worked intensively with African artists and curators since the late eighties of the last century. At that time I met Fernando Alvim, an Angolan artist who had founded a centre for contemporary African art in Brussels, where I was living, and who was very keen at the time to create a road between the two continents on which, as he pointed out, you could travel in both directions. This centre, which existed in various forms in Brussels until 2005 and was later relocated to Luanda, was an international meeting place for artists from Africa and the African diaspora. I spent nights talking to many of these artists and intellectuals about topics as diverse as neo-colonial politics and the influence of the Nkisi spirits. Some inspiring relationships developed, for example with Simon Njami, who now plays an important role in contemporary art and is currently involved in the selection of the curator for the next Documenta and who wrote a brilliant article about my work in which he even went so far as to claim that my work in South Africa had made me an African, whatever that means. I exhibited my work half a dozen times at Camouflage, as the centre was called in its late phase, and travelled to some African countries back then, to Egypt, which is all too easy to forget is an African country and plays an important role if you have an alchemical practice, because the roots, at least of one of the best known forms of alchemy, are in Africa. One should also make more connections between Vodun practices and alchemy. Suzanne Preston Blier does this in her book “African Vodun” but otherwise little reference is made to it. I have worked in Ghana too, where I explored the influence of religious imperialism in The Trustfiles. This work led to my participation in the first Luanda Biennale in Angola. South Africa has been a major influence, which I visited several times and where I completed a residency that led to an exhibition in Johannesburg and later to the publication of a book dedicated to this work. However, the work on my video installation Collision Zone, with which I represented Luxembourg at the 2009 Venice Biennale and in which I juxtaposed African immigration movements with the shifting of tectonic plates, seems to me to be the most significant. It revolved around the political and geological tensions in the Mediterranean that are literally turning this region into a collision zone. I experienced some of these tensions first hand when I was arrested in Ceuta on the Moroccan border for illegally filming there and could literally feel the paranoia that Fortress Europe has to militarily secure its borders.

As you can see, there are many connections to Africa. It’s also important to mention the proximity of my sculptural work to Vodun. It’s a troublesome thing with such influences because most people nowadays immediately assume cultural appropriation when you mention them. But, as my Angolan friend said, the motorway goes both ways, and if you don’t mind Africans adopting European working methods, you shouldn’t mind Europeans doing the same with African ones. We have often talked about Oswald de Andrade’s “cannibalist manifesto”, the basic idea of which is that Brazil’s history of “cannibalising” other cultures is its greatest strength. We are all cultural cannibals, but I don’t think we can adopt the strategies of other cultures one-to-one in other contexts, we have to make them our own and make something personal out of them. However that may be, I have tried to find out as much as possible about the sculptures called Bocios, which play a central role in Vodun. They help me to get a view of art objects that is not exclusively characterised by their aesthetics, but by the materials that these objects are made of or that are added to them to give them a magical charge. In addition, the transience that comes into play in Bocios is a central element of my work, especially that which I develop here in the Ardennes Forest.

Can you elaborate on your process of image creation and the role divine images play in ritual? How does this lead to communication and perception of the “other”?

This process flows directly from what I mentioned in the previous answer at the end. Sorcerous art is a dialogue with the visible and invisible beings that populate the forest, in which power relations are negotiated. It is about entering the so-called “imaginary realm” through a shift in consciousness. There we can connect with the forces at work in the otherworld and give them the opportunity to express themselves in the world of images. They do this by guiding our hand, so to speak, in the realisation of the images.

However, to bring this potential to full fruition, we need to nourish the images through offerings and animate them through rites, which in some cases should be performed daily when we are dealing with beings that we have closely bound to us, and in other cases only seasonally. In some cases, we can also put the images into a deep sleep, in which they remain for years before we awaken them again and make them affective. In any case, only through constant communication do images come alive and affect us in such a way that they truly become a part of our lives. As always with sacred art (or divine images as you call it), but especially in our atomised western society where community rites have largely disappeared from social life, the question arises as to whether and how we can share living images. In many cases, it is probably best to live with them alone, in a society that has no understanding of such approaches, or at least has lost it. But ultimately the question of whether we should remain alone with the sacred images or share them is one that I am confronted with again and again when a new work is created.

Can you discuss your sacred goal? The creation of a work of art from the blackness itself? The drawing down of the eye into the material realm of the forest?

My ultimate goal is to connect with the sacred blackness of the universe through alchemical thinking and practice, so that when I die, I return to it and experience this return as a homecoming. For Socrates and Plato, philosophy is a preparation for death. I think this is all the more true when we deal with occult philosophy and black alchemy. The blackness inherent in this term and underlying my art is often interpreted as pessimistic or nihilistic, but this is a misunderstanding. The aim is to translate the human back to nature, or the chthonic universe or whatever we wanna call it.

By drawing the eye down into the material realm of the forest, you refer to the black sculptures that I have painted with bone charcoal and which I have installed and anchored here in the forest clearing. Depending on the light and weather conditions, they are sometimes so dark that they act like negative matter and draw the eye like a black hole into the depths of the forest, which I equate with the underworld. I spend a lot of time meditating on this blackness and connecting it to the darkness in my body. We carry the blackness of the universe within us, and my practice is largely about nurturing and celebrating it. And indeed, the ultimate goal is to create a work of art from this blackness, but I will fail.

Can you discuss the politics of your work? The radical inclusiveness and the rejection of traditionalism? And your thoughts on the current occult landscape in terms of politics?